INSIGHT

The true cost of rising inequality

Wealth and income inequality has never played a major role in the health of financial markets. That is about to change.

The impact of COVID-19 will exacerbate inequality in the Asian region, which was already on the rise before the pandemic. The disproportionate impact on contact-intensive industries which predominantly engage workers with lower skill and wages, low spending by businesses, and accrual of financial market gains to higher income groups will all be ongoing factors.

Closing the gap will require higher social spending. A durable step-up in social spending was also a stylised feature of fiscal policy in the region after the Asian and Global financial crises. Even so, social spending in Asia remains considerably lower than in the OECD economies.

Whether higher social expenditure is funded by higher taxation rates, larger budget deficits, or a combination of the two, there will be implications for growth and fixed income markets in the region.

Higher budget deficits may also require further accommodative monetary policy, particularly when the currently favourable liquidity conditions recede.

Sources

The COVID-19 pandemic is set to accentuate income and wealth inequality via at least three sources. The best-documented of these is the very nature of the pandemic, which has taken a disproportionate toll on contact-intensive sectors such as tourism, recreation, retail services and domestic help.

Youth and female participation rates are higher in these sectors. In contrast, higher skilled and higher paying employment has been shielded from the pandemic as these jobs are less location specific.

The skill-based divide present before the pandemic has widened even further. It is manifest in various indicators ranging from reduced hiring of low-skilled temporary workers, a rise in the labour intensity of agriculture in India and Thailand, the widening gap between earnings of the top and bottom quintiles of workers, and the comparatively greater rise in unemployment rates among less educated workers.

The second and relatively less-documented source of inequality is the unprecedented depth of the recession and the associated deterioration in corporate performance. The recovery will require significant restraint on expenditures, including on wages and salaries.

Thirdly, the performance of financial assets is becoming a source of inequality. The rebound in equities after a steep dive in the first quarter of 2020 is exacerbating inequality as it has diverged from the real economy.

This has been largely driven by low interest rates and quantitative easing by central banks. As equities are predominantly held by higher-income groups, and the savings of the lower-income groups are concentrated in banks deposits, rebounding equities amidst low interest rates have likely worsened inequality.

Overall, the ongoing and anticipated further rise in inequality is consistent with previous pandemics. In a study on the distributional impact of pandemics on employment and income inequality, the IMF found the net Gini coefficient rose nearly 1.5 per cent in the five years following the pandemic.

The study found pandemics had a disparate impact on employment of people with different levels of education, which is an indicator of skill level. The employment of those with basic education fell by 5 per cent over a five-year period, while those with advanced skills were scarcely impacted.

Already

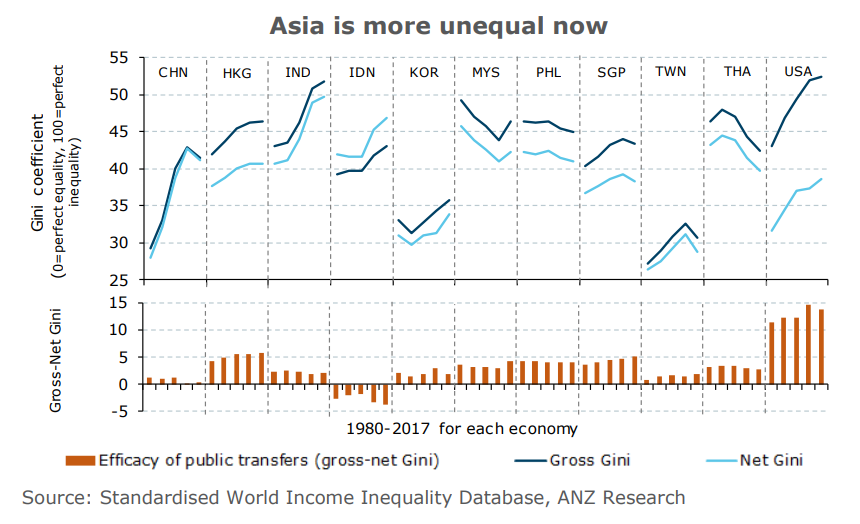

High income inequality that cannot be fully addressed by the existing systems of tax and benefits was already a problem for the region prior to the pandemic. Income inequality as measured by Gini coefficients has risen since the 1990s, and though it seems to have receded in some economies since 2010, the longer- term pattern suggests the region’s growth has not been particularly inclusive.

At the level of individual economies, we note income inequality has risen between 2000 and the subsequent 15 years or so in Mainland China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, and South Korea. The increase has been more than two points on the Gini index for China and South Korea and more than five points for India and Indonesia. Considering China, India, and Indonesia are also the most populous, an important corollary is, on an aggregate or population-weighted basis, inequality has increased in the region.

Another facet of income inequality in Asia is the limited efficacy of fiscal policies in closing the income gap. The efficacy, as measured by the difference between the gross and net Gini index, is significantly smaller in all Asian economies than in the US.

Based on available data, it is clear social spending in all Asian economies is well behind the OECD level of 17 per cent of gross domestic product.

Social

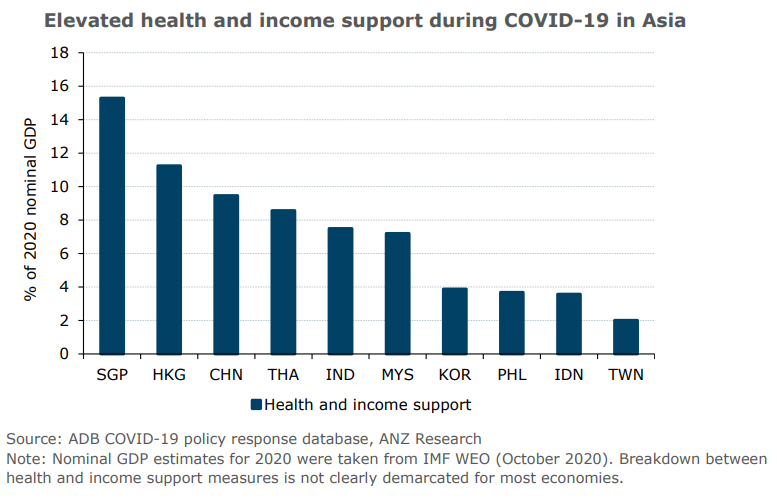

Social spending measures in the region have been augmented with uncharacteristic alacrity in the wake of the pandemic. The scale of emergency fiscal measures has exceeded 10 per cent of GDP, and apart from enhanced spending on healthcare, they also encompass income support measures including unemployment benefits, direct cash transfers, wage subsidies, and guarantees on borrowings by households and small and medium enterprises. As SMEs are the largest employers, mitigating the risk of bankruptcies was viewed as critical in preventing an escalation in unemployment.

The COVID-19 policy response tracker of the Asian Development Bank reveals the elevated scale of such intervention. The measures targeted at providing health and income support range from 2 per cent to 15 per cent of GDP.

At the upper end of the spectrum are Singapore, Hong Kong and China while at the lower end are Taiwan, Indonesia and the Philippines.

It is unlikely policymakers intended these steps to explicitly address income inequality in the region. However, even after growth has recovered, a rise in income inequality over the medium term seems inevitable, which will warrant redressal for socio-political reasons.

ANZ Research’s view is while social spending in Asia is unlikely to mirror OECD levels, it is still slated to secularly rise in the coming years.

Implications

If and how this impacts public finances is a policy choice between higher tax rates or durably higher deficits, the macroeconomic implications of which also differ.

Higher marginal tax rates are typically associated with slower growth owing to their adverse impact on savings and investment. In general, the region’s tax-to-GDP ratio is lower than in advanced economies due to lower taxation rates, smaller tax base and weak compliance in some economies like India, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

These deficiencies also suggest major tax reform will be essential to raise the tax-to-GDP ratio to the extent it can meaningfully fund enhanced social spending programmes. Although eventually inevitable, the complexity and time involved in overhauling the tax system suggests a possible tendency to accept higher budget deficits in the more immediate term.

It is all the more likely as most economies have moderate public debt-to-GDP ratios. In ANZ Research’s view, it is entirely possible social protection in the region rises durably between 1 per cent and 3 per cent of GDP on average, resulting in a commensurate rise in budget deficits.

However, higher budget deficits will not be neutral for fixed income markets as they were in 2020. The favourable combination of large output gaps, weak credit demand, and large balance of payments surpluses have allowed for a smooth funding of surging fiscal outlays. This backdrop has also allowed central banks to pursue unconventional monetary policies with minimal impact on bond yields.

This favourable backdrop is likely to persist for much of this year as well, but cannot be assured beyond that. Thereafter, funding requirements will either pressure bond yields higher or warrant continuation of unconventional monetary policies to some degree.

In reality, the economic effects of unconventional monetary policies are not entirely dissimilar to that of a conventional rates-based policy, and therefore, have the potential to conflict with inflation targeting frameworks in the region.

Sanjay Mathur is Chief Economist Southeast Asia & Dhiraj Nim is an FX Analyst at ANZ

This story is an edited version of an ANZ Research report. You can read the original report HERE.

This publication is published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia. This publication is intended as thought-leadership material. It is not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in this publication is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in this publication constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of publication. While this publication has been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of this publication or the use of information contained in this publication. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with this publication.