INSIGHT

The legacy challenges of China’s new economy

It is widely believed the rise of China’s new economy is crucial for the Asian giant to lift its productivity over the long run, avoid a ‘middle-income’ trap and counter external shocks.

Many think China’s new economy is equivalent to the digital economy but China itself has a wider definition: besides tech conglomerates such as Alibaba and Tencent, business sectors such as express-delivery services and new energy vehicles are also considered to be players in the new economy.

Official data suggest China’s new economy contributed 1.5 percentage points to overall growth in 2019, which was adequate to cushion negative shocks stemming from China-US tensions.

Although the new economy could help secure stable growth rates, an unknown factor is whether it will be deflationary and lead to a low interest-rate environment as it did in the US. This requires flexible and dextrous policy-making.

Inflation

The US dotcom boom brought a mix of high growth and low inflation. It also triggered debate about whether the rise of the new economy has changed the fundamental relationships between growth, inflation, and employment, and hence the course of monetary policy.

During the 1990s, the US economy presented a seemingly impossible mix of high growth (with low volatility), low unemployment, and low inflation, contradicting the Phillips curve which posits an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment.

A high-tech economy could lead to very high fixed costs and very low marginal costs; a trend that can produce a virtuous cycle where rising demand will produce higher efficiency, higher returns, and lower prices, leading to even higher demand and stable growth at a certain level.

High growth and low inflation could co-exist. Still, whether the new economy is deflationary or not is unclear. Some research papers have concluded high-tech is a major factor driving down US inflation, but there is also evidence that other factors may have contributed to the downtrend.

China’s accession to the WTO and the movement of its supply chains toward developing economies has suppressed import inflation in the US. An aging population, de-unionisation of the work force, and changing consumption patterns could also have contributed to the structural change in US inflation.

ANZ Research is inclined to agree that technological progress will exert downward pressure on China’s inflation. Structural factors, such as demographic changes and the recent shift of manufacturing supply chains out of China, may further affect inflation negatively over the long run.

A critical implication of low inflation is a prolonged period of low interest rates. In an environment of stable growth, low inflation and low interest rates, China’s monetary policy will need to be carefully managed.

Going forward, the People’s Bank of China may find it more challenging to distinguish between transitory and permanent changes in productivity. In the event of a permanent increase in productivity growth, the PBoC may need to be more generous when stabilising inflation while allowing output to move to its new long-run growth path. However, the flip side of accommodative monetary policy over the long term is that it can lead to excessive liquidity and asset price bubbles.

The new economy can also affect the channels via which monetary policy works. China has launched a digital currency which could lift the money multiplier and move the country closer to a ‘cash-lite’ society. It could also bring about negative interest rates and provide an opportunity for China to avoid the liquidity trap.

Hub

During his recent visit to Shenzhen – a pilot city in China’s 40-year-old ‘open-up’ policy – Chinese President Xi Jinping reiterated the idea of developing Shenzhen into a global high-tech hub. This highlighted the importance of the new economy in reshaping Shenzhen’s growth path over the next decade.

The city has undergone a transformation from a low value-added production-led growth model to a technologically innovative and high value-added manufacturing-led model.

As the headquarters of giants like Huawei and Tencent, Shenzhen demonstrates the crucial role of the new economy in China.

Indeed, gross domestic product growth of the IT and software sectors (key components of China’s new economy) rose 18.8 per cent year on year in the third quarter of 2020. Double-digit growth has not faltered since 2015 despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cutting edge

The term ‘new economy’, which emerged in the 1990s, describes high-growth industries with cutting-edge technology and drive growth and productivity, particularly the rise of personal computers and the internet.

In the 2000s, the new economy is more about the ‘digital economy’. A narrow definition of the digital economy is limited to the ICT sector: the internet, telecommunications, IT services, hardware, software, and so on.

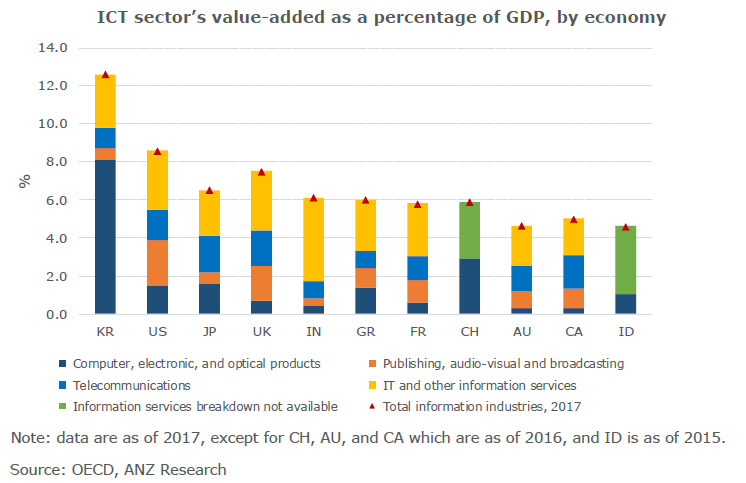

The value added of these sectors is relatively easy to attain and generally comparable across countries. According to an OECD estimate, the size of the digital economy (based on this narrow definition) was about 6 per cent of China’s GDP in 2016, compared to 8.6 per cent of the US economy.

The OECD has also suggested a more comprehensive definition of the digital economy, which: “incorporates all economic activity reliant on, or significantly enhanced by the use of digital inputs, including digital technologies, digital infrastructure, digital services and data. It refers to all producers and consumers, including government, that are utilising these digital inputs in their economic activities.”

Different countries have different ways of evaluating the components of the digital economy. China’s definition accounts for more than 36.2 per cent of GDP (estimated by CAICT), while the US BEA’s latest method suggests its digital economy accounts for 11.3 per cent of overall GDP. These differences in the reported size of the digital economy do not reflect different data sources or methodologies, but different definitions.

Various international approaches suggest that China’s digitalisation rate is ranked in the middle of the global spectrum. However, these tend to neglect regional and industry discrepancies within China, because large cities are much more digitalised than small ones.

At the corporate level, Chinese high-tech giants, including Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei, are global leaders in several strategic areas, like ecommerce, 5G, cloud computing, and processing capacity of online payment solutions. They are also among the world’s largest spenders on research and development (Global Innovation Index, 2020).

NEW

China’s measure of the new economy encompasses more than the digital economy. The so-called “Three NEWs” (三新经济) refers to new industry; new types of businesses; and new business models.

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) also defined the sector/industry coverage in 2018. Besides digital-based sectors, new energy vehicles (NEV), healthcare services, express delivery services, long-term apartment leasing, customised dining, ecotourism and comprehensive business management were all recognised to be part of China’s new economy.

According to NBS’s estimate, the “Three NEWs” amounted to 16.2 trillion yuan (16.3 per cent of GDP) in 2019, up 9.3 per cent year on year. This suggests this part of the economy contributed nearly 1.5 percentage points to overall growth, which was adequate to help cushion against negative external shocks such as the US-China trade spat – a disagreement which once led market players to believe that the tensions could erode China’s GDP growth by 1.0 to 1.5 percentage points.

Some sector-specific data can provide a direct sense of how quickly China has embraced these changes. According the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), China’s online retail sales reached 10.6 trillion yuan in 2019, more than doubling within four years. Mobile payments also rose to 347 trillion yuan, up 25 per cent year on year.

Productivity

The new economy is making significant changes to lifestyles and lifting productivity in China, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 outbreak when most people had to work from home.

For instance, phone calls, video conferences, the Internet and VPNs made it possible for millions of people to carry out their tasks or participate in meetings from any location at any time of the day.

According to IMF research, a single percentage point increase in the digitalisation of China’s economy is associated with an increase of 0.3 percentage points in GDP growth, with a two-year lag.

Lowering transaction costs, decreased information asymmetry and enhanced production efficiency are the major channels via which digitalisation will improve efficiency and productivity.

China’s economy has commenced a structural shift from industrialisation to services-led growth, but the latter usually yields much lower productivity growth. Therefore, China’s potential GDP growth will inevitably slow, which could be reinforced by rising incomes and the economy’s edging closer to the technology frontier.

However, the rise of the new economy could moderate the slowdown by improving sector-specific productivity and helping to provide a buffer against external shocks.

Betty Wang is Senior China Economist and Bansi Madhavani is an Economist at ANZ

This story is an edited version of an ANZ Research report. Click HERE to read the original report.

This publication is published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia. This publication is intended as thought-leadership material. It is not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in this publication is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in this publication constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of publication. While this publication has been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of this publication or the use of information contained in this publication. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with this publication.