FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS GROUP NEWSLETTER

A PILLAR TO LEAN ON: AUSTRALIA’S APPROACH TO IRRBB HOLDS VALUABLE LESSONS FOR GLOBAL BANKS

Download

PRACTICES IN MANAGING THE INTEREST RATE RISK IN THE BANKING BOOK (IRRBB) REQUIREMENTS

Managing interest rate risks, a challenge for banks and financial institutions at the best of times, has taken on a fresh urgency amid the novel coronavirus (Covid-19)1 outbreak. Recognising the unprecedented threat the disease’s spread poses to their respective economies and markets, most central banks around the world have slashed interest rates in a bid to boost liquidity in the financial markets to support economic growth.

This globally coordinated action provides a stark yet appropriate backdrop to discuss the relative merits of the two main approaches adopted by banks and their regulators to the Basel Committee’s regulatory framework for managing interest rate risk in the banking book (IRRBB).2

Additionally, ongoing consultations by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA)3 – whose approach to IRRBB stands apart from other regulators worldwide and has proven successful in helping Australian banks manage risk efficiently - have the potential to influence the global capital requirement standards set forth by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), and bring about changes to regulatory approaches across markets around the world.

THE IRRBB ETHOS

The IRRBB framework, originally introduced in 2004 and revised by BCBS in 2016, aims to ensure banks have sufficient capital to absorb or withstand the risks arising from their exposure to interest rate movements in the banking book positions. It does so by defining the various sources of interest rate risks; identifying the assets and liabilities on a bank’s balance sheet that can be subject to these risks; and, prescribing ways to measure the risks with two specific metrics.

The risks that the IRRBB framework is designed to assess and manage include repricing risk or gap risk, yield curve risk, optionality risk and basis risk.4 The key measure that helps in this exercise is the change in Economic Value of Equity (EVE), which focuses on the risk to net worth arising from all repricing mismatches and other interest rate sensitive positions over the long term. The other measure is the change to Net Interest Income (NII), which is measured by the changes in Net Interest Income or margin, and focuses on the impact of changes in interest rates on accrual or reported earnings in the near term.

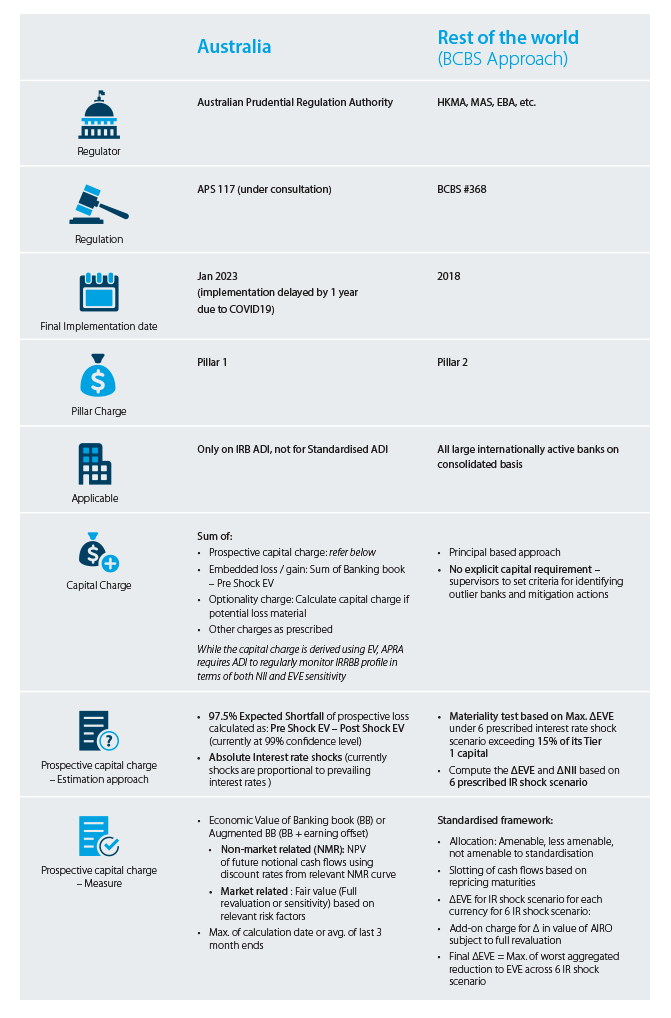

FIGURE 1:

IRRBB Regulations Across Key Jurisdictions

Source: APS 117 – Current Consultation, Basel Standard 368 – IRRBB – April 2016, MAS, HKMA, IRB – Internal Rating Based Approach; ADI – Authorised Deposit-Taking Institution;

EVE– Economic Value of Equity; NII – Net Interest Income; IR – Interest Rate; AIRO – Automatic Interest Rate Options;

While most regulators around the world have adopted these metrics to manage the capability of their banks to cope with interest rate volatility, their approaches to following the Basel Committee guidelines - categorised as Pillar 1 or Pillar 2 - have diverged.

The Pillar 1 approach requires banks to reserve capital by adopting the agreed approach prescribed by the regulator. In doing so, it seeks to harmonise the variations with a pre-determined approach – which considers each bank’s exposure - that specifies the amount a bank has to hold as reserve capital. For such banks, the total Risk Weighted Assets (RWA) includes a portion that is calculated to account specifically for IRRRB risks.

The Pillar 2 approach, on the other hand, sets the broad principles and allows banks to follow a set of internal measures, where banks do not need to reserve IRRBB capital in the Pillar 1 RWA requirements. Thus, the Pillar 2 approach relies on banks to calculate the IRBB capital they need based on their in-house management practices and processes, with periodic checks by the regulator to ensure sufficient capital is maintained against the banks’ internal thresholds.

PICKING THE RIGHT APPROACH

Currently, APRA is the only regulator to adopt the Pillar 1 approach for IRRBB. APRA’s decision was driven by its finding that IRRBB risk was significant for Australian banks and yet they were allowed to use their internal models to gauge their Banking Book interest rate risk exposures and not to reserve capital for these exposures.

As a result, major Australian banks have prescribed RWA requirements coming from their Banking Book interest rate exposures, prompting them to actively manage their RWA or capital requirements. Further, these measures are disclosed to the markets every quarter.

While the Basel Committee concluded that the Pillar 2 approach would be better suited to capture the diffuse nature of IRRBB,5 the performance of Australian banks can be viewed as a vindication of APRA’s decision to adopt the Pillar 1 approach.

With their upgraded risk models, the country’s banks have succeeded in managing their exposure to risk, in return saving millions of dollars in capital requirements.

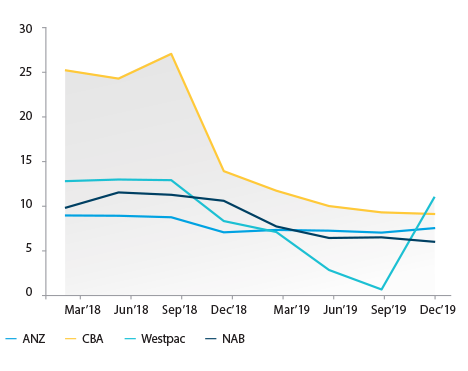

For the quarter ending March 2019, while ANZ cited lower exposure to yield curve risk and repricing as drivers of a reduced IRRBB charge, National Australia Bank (NAB) reduced its IRRBB RWA by 22% y-o-y while Westpac slashed IRRBB RWA by 45% y-o-y. Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) achieved the greatest savings of the Big Four Australian banks, achieving a 54% y-o-y reduction in IRRBB RWA.6

These outcomes highlight the effectiveness of mandating explicit capital requirements as espoused by the Pillar 1 approach, and its ability to inspire greater discipline and active management of IRRBB compared to the more opaque nature of the Pillar 2 approach.

FIGURE 2:

IRRBB RWA Movement of Australian Major Banks

Source: Company financial reports

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

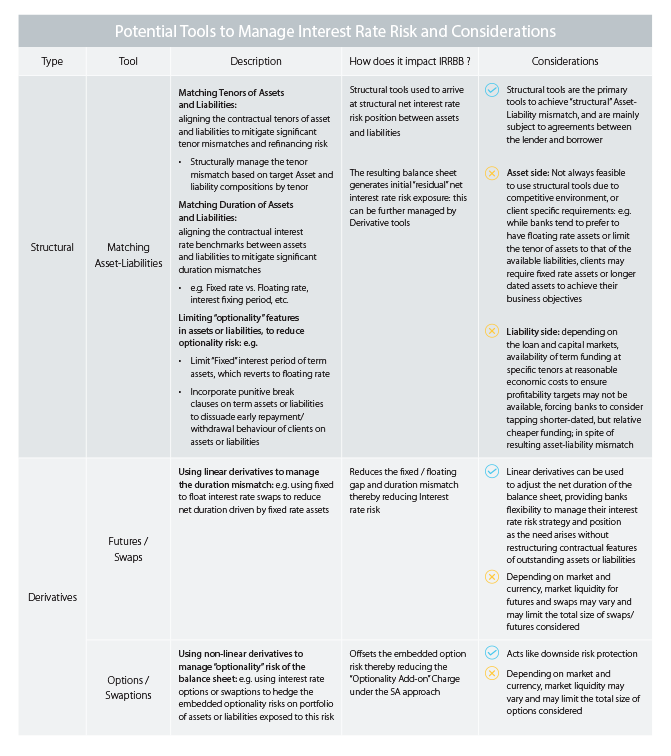

Banks typically turn to a range of structural as well as derivative tools to manage IRRBB, with certain tools being best suited to manage a particular type of risk. For instance, linear derivatives such as interest rate swaps, futures and foreign exchange swaps are geared towards reducing basis risks as well as gap risks, which tend to be the most common type of IRRBB. Non-linear derivatives, such as interest rate options and swaptions, can be used to effectively manage optionality and behaviour risks.

While banks across the Asia Pacific (APAC) region rely more on structural tools, Australian banks are known to consider a combination of both structural as well as derivatives tools. Indeed, derivatives form a major part of the arsenal used by the country’s authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) to manage interest rate risk with interest rate swaps and futures, making up a bulk of the mix. Futures are a common approach to hedging the bulk of interest rate risk as they are very liquid. Another significant management tool – especially when banks are raising funding – is the crosscurrency interest rate swap.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

WITH THEIR UPGRADED RISK MODELS, THE COUNTRY’S BANKS HAVE SUCCEEDED IN MANAGING THEIR EXPOSURE TO RISK, IN RETURN SAVING MILLIONS OF DOLLARS IN CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

FIGURE 3:

Tools to manage IRRBB and Considerations

Sources: ANZ Analysis

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“OF COURSE THE SUITABILITY OF A TOOL ALSO DEPENDS ON THE RISK MEASURE A BANK WANTS TO OPTIMISE OR MANAGE. LINEAR DERIVATIVES SUCH AS FUTURES, INTEREST RATE SWAPS OR FORWARDS CAN BE USED TO ADDRESS REPRICING AND YIELD CURVE RISK, BY FAR THE LARGEST CONTRIBUTOR TO IRRBB, WHICH IMPACTS EVE AND NII”, SAYS ALEX ZILBERMAN, ANZ’S HEAD OF NON-TRADED MARKET RISK.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Further differences can arise in terms of the banks’ size of operations and the markets they serve. For instance, banks in Australia have relatively low optionality compared to, say, US banks because long dated fixedrate mortgages with free pre-payment features are not a major feature of the Australian market. Therefore, to that extent embedded optionality risk is relatively small for Australian banks and the focus has historically been on EVE. However, in terms of risk management requirements, APRA expects risk appetite to be measured in a way that covers both EVE and NII.

Across APAC, which is home to many global banks as well as regional players, the use of derivatives by the latter group would be relatively limited. These regional banks also have relatively less exposure to optionality with the bulk of their interest rate risk originating from their primary business, which is mainly comprised of deposits, mortgages and loans to corporates. The main challenge for such APAC banks is to manage the linear interest rate risks on their books and any risk arising from the benchmarks used on loans, which can be managed with interest rate swaps and basis rate swaps.

TRANSPARENCY AND PREPAREDNESS

ANZ has a robust risk management governance framework in place with The Board of Directors having ultimate responsibility for ANZ’s Risk Management Framework, and for oversight of its operation by management. Key IRRBB metrics form part of the overall set of the Key Material Risks with corresponding specific risk appetite levels. These metrics are then cascaded down through the organisation via the respective delegation structure.

The risk limits are carefully aligned and calibrated to a division’s risk appetite level, which is reviewed regularly. Such measures are a direct outcome of APRA’s decision to embrace and enforce the Pillar 1 approach, which espouses and encourages active management, better discipline and greater transparency across all levels of a bank’s risk management process. Because, ultimately, it is the senior management’s responsibility to effectively manage a bank’s approach to ensure its various regulatory7 and business8 objectives - which can sometimes be seen to contradict each other - are met in an optimal manner. “In order to do so, it is advisable for a bank’s leadership to call on all the resources and tools at their disposal to develop and align the risk management and business strategy of the bank and to do so in a clear and transparent manner”, says Bill Waters, ANZ FIG Coverage in Australia.

Finally, as Australia’s banking sector winds through APRA’s consultative process to further strengthen and streamline its risk management practices, it provides an ideal opportunity for banks across APAC and their senior management to absorb and adopt proven best practices for their respective markets. This will prove an invaluable exercise for equipping their institutions to successfully adopt future regulatory changes to the process of managing IRRBB, including for any potential transition from a Pillar 2 to a Pillar 1 approach.

1 https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

2 https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d368.htm

3 https://afma.com.au/policy/member-news/2019/2019_09_APRA_IRRBB_Consultation.pdf

4 https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d319.pdf

5 https://www.moodysanalytics.com/-/media/whitepaper/2016/summary-of-bcbs-interest-rate-risk-in-the-banking-book-directive.pdf

6 https://www.risk.net/risk-quantum/6645851/aussie-banks-crush-irrbb-capital-charges

7 For example, Capital Adequacy Ratio, Net Stable Funding Ratio, Liquidity Coverage Ratio, IRRBB, etc.

8 For example, Shareholder Value creation, ROE or Risk Adjusted Return targets, etc.

CONTACTS

This publication is intended as thought-leadership material. It is not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in this publication is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in this publication constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of publication. While this publication has been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of this publication or the use of information contained in this publication. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with this publication.