INSIGHT

Can Japan solve its demographic issue with 1s and 0s?

Japan is a world leader in two opposing growth dynamics – a declining workforce, which is a drag on productivity, and a leading investor in robotics, which is beneficial to it. The dichotomy is rather stark.

The adverse implications of an ageing population for growth are some of the drivers behind Prime Minister Shinzo Abe administration’s ambitious ‘Society 5.0’ strategy.

The plan hopes to see increasing technological change in Japan across a swathe of industries with the aim of improving quality of life measures. The country is a relatively unique case in the world given its negative labour-force dynamics.

But to succeed productivity - supported by investment in automation, AI and technology - will need to feature strongly as an engine supporting long-term economic growth.

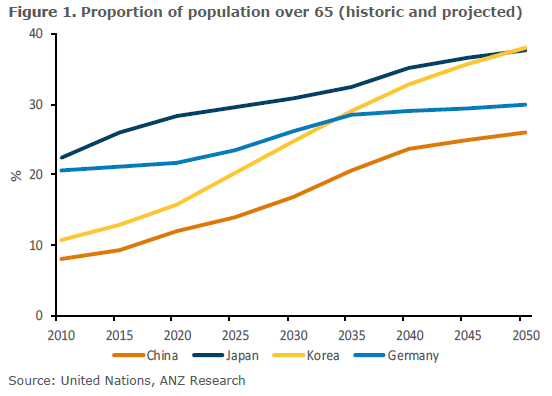

Should Japan pull it off, the experience could hold valuable lessons for economies such as China, South Korea and Europe, which are facing similar demographic trends.

The Society 5.0 program envisages greater adoption of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics and big data to enhance long-term productivity. Technology will help fill the void of a declining workforce and/or augment the existing labour force.

Japan’s population fell by a record-breaking 264,000 to 126.4 million in 2018. The population is set to decline further in coming years given the current birth rate (1.4) is significantly below the steady-state rate (2.1). By 2050 Japan’s population is expect to fall below 100 million.

In 2015 27 per cent of Japan’s population was older than 65 and this is expected to rise to 38 per cent by 2050.

Next five

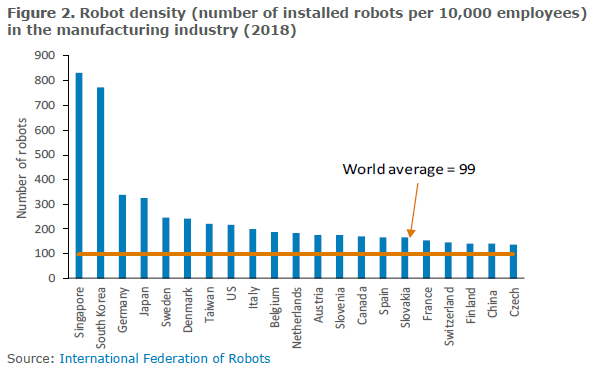

Automation and robotics are not new for Japan. In 2018 the country exported $US2 billion worth of industrial robots - more than the next five largest exporters combined.

Japan is one of the most-integrated economies in the world in terms of ‘robot density’ – measured as the number of robots relative to humans in manufacturing.

Traditionally much of Japan’s investment in robotics has been export-orientated, especially in automotive and electronics. Very little investment has been made by the much-larger services sector which accounts for almost three-quarters of the economy.

The lack of technology investment by the service sector likely contributes to the sizeable productivity gap between that industry and manufacturing.

There has been very little productivity growth in the services sector over past couple of decades. This lack of investment may partly reflect the fragmented state of many service-based industries and the lack of competitive domestic pressure.

Productivity in the services sector has also lagged that of other main advanced economies. Notably the labour productivity of the non-manufacturing sector in Japan is about 60 per cent of that of the United States.

There would seem room for both a catch-up and an organic improvement in the underlying productivity of the service sector. This should yield substantial dividends to gross domestic product growth given the service sector accounts for nearly three quarters of Japan’s economy.

Revolution #5

Under a successful Society 5.0, Japan will be a super-smart society where technologies such as big data, Internet of Things (IoT), AI and robots are present in every industry and across all social segments. Everyday life will be more comfortable, efficient and sustainable.

As part of this integrated strategy the government has produced a number of detailed and ambitious reports, including: IT Strategy for Data Utilisation, Robot Strategy and an Artificial Intelligence Technology Strategy.

Recent surveys highlight a lift in both actual and planned capex spending on new technology. This trend is notable for small and medium enterprises that need to compensate for scarce labour and stay competitive.

Game-changing five

Japan’s comprehensive blueprint for Society 5.0 includes strategic objectives and implementation scenarios. Some examples of current and future integration include:

• electronic payments and self-checkout registers in retail outlets;

• touch-screen menus in hospitality to streamline operations;

• drones to deliver goods in remote areas, survey property and support disaster relief;

• online medical care to enhance best practice, reduce travel, increase support to less-mobile patients and conveniently offer 24/7 monitoring, including nursing robots; and

• autonomous transport (driverless buses, cars and trains).

The empirical evidence on the impact of automation and technology on jobs is mixed. In the short term some workers will be more vulnerable to displacement so there are likely to be transition costs leading to undesirable consequences of lost income, income polarisation and rising inequality.

In the long run however technological advances boost productivity which over time creates new jobs, allowing incomes and living standards to rise.

A 2017 RIETI discussion paper, using Japanese prefectural data, found increased robot density in manufacturing to be associated not only with greater productivity but also with local gains in employment and wages.

This suggests embracing innovation outside of manufacturing should also provide long-term dividends.

Technical innovation is also necessary to help alleviate a declining workforce but the Japanese government will need to carefully manage the transition.

Strong and effective safety nets will be crucial to support workers displaced or disadvantaged. In addition, the government can take a proactive position in educating and reskilling workers to enable them to take advantage of jobs in a high-tech world.

Tom Kenny is a senior economist at ANZ

This is an edited version of an ANZ Research report. You can read the original report HERE.

This publication is published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia. This publication is intended as thought-leadership material. It is not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in this publication is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in this publication constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of publication. While this publication has been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of this publication or the use of information contained in this publication. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with this publication.