Budget 2020

Making a recovery

The 2020-2021 Australian Federal Budget appears focussed on engineering a private-sector recovery.

Fiscal conservatism has been tossed aside to combat the health and economic effects of the pandemic. However, there is less direct-income support in the current quarter than had been expected, potentially creating risk around the impact of a fiscal cliff – a risk that may not be offset by businesses bringing forward investment spending soon enough.

But there are many moving parts to this COVID economy. Given all the pluses and minuses, ANZ Research is comfortable with its current GDP forecasts, albeit with a different possible mix.

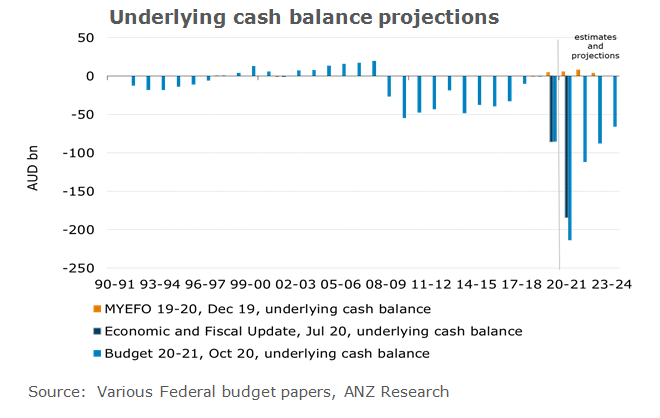

Australia’s underlying cash deficit is now expected to reach $A214 billion in 2020-21 as this budget increased spending again and tax cuts were introduced or brought forward.

This is a smaller deficit projection than expected this year, given Treasury don’t think revenue will fall as far as ANZ Research thought, while a number of tax measures don’t kick into top gear until 2021-22.

Gross debt will rise to 55 per cent of GDP, a level not seen since the 1950s, although with interest rates historically low, the debt burden remains low at around 1 per cent of GDP.

Extensive support

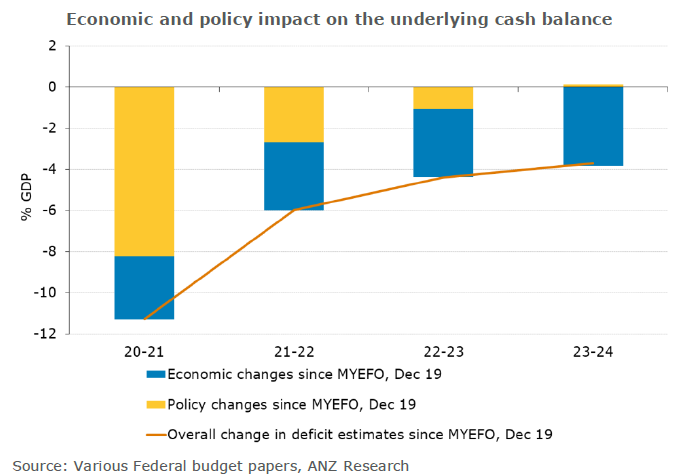

About three quarters of the deterioration in the estimated underlying cash balance for 2020-21, since the Mid-Year Economic and Financial Outlook was published, pre-COVID , in December 2019, is due to policies put in place before the budget was announced.

Of these, the $A101 billion JobKeeper and the $A32 billion boost to cash flow for employer measures were the largest and due to their unprecedented cost, not repeatable. Since the July update, policy decisions will reduce taxes by an estimated $A8.6 billion while spending has been increased by an estimated $A34.2 billion for 2020-21.

As JobKeeper comes to an end the variation in spending is much smaller, again highlighting that even though this is a big-spending budget, it was the policies put in place before today that really moved the fiscal dials.

COVID-19 related support is expected to take spending to a historically high peak of 34.8 per cent of GDP in 2020-21. Due to the temporary nature of many of the policies, this falls quickly to 28.1 per cent of GDP the year after and continues to decrease based on current policy settings.

Receipts on the other hand change less dramatically and are not expected to move to the lows recorded in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis.

This represents something of a risk to the fiscal outlook. It was the revenue side of the fiscal equation that often underperformed relative to the forecasts in the post GFC period. All up, the task of fiscal repair may again prove more difficult than expected, as has been the case for much of the past decade.

The bigger error would be to force fiscal consolidation to be faster. ANZ Research thinks the government is well aware of this risk, as reflected in the changes to its fiscal strategy – which postpones a focus on” stabilising gross and net debt as a share of the economy” until unemployment is “comfortably below 6 per cent”.

Credible amid uncertainty

The economic forecasts underpinning the budget appear quite reasonable. For 2020-21, the government expects real GDP to contract by just 1.5 per cent, which is not as weak as ANZ Research’s forecast of -3.8 per cent and the Reserve Bank of Australia’s of -3 per cent.

Recent news has been more positive on the economy, and in particular on the virus numbers, so while this number is higher than our own, it looks defensible.

Further out, the expectations for real GDP look broadly in line with our own thinking, with a strong recovery in 2021-22 and moderation to still-solid rates of growth in the following two years.

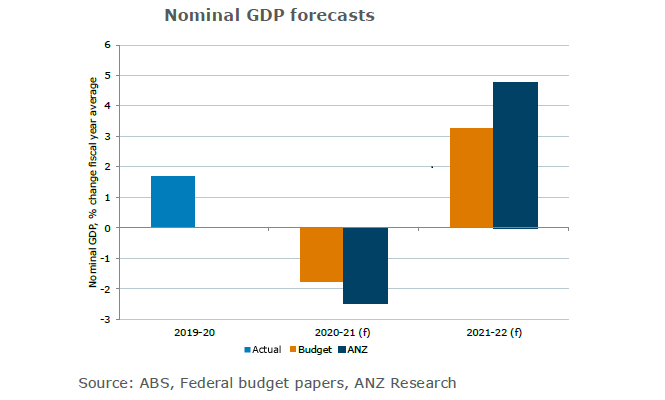

For nominal GDP, which is the key parameter for the deficit, the Government’s forecasts are a little higher than ANZ Research’s for 2020-21, although they are a bit lower in 2021-22, given the expectation that the terms of trade falls a sharp 10.75 per cent.

The government is forecasting 338,000 workers gain employment over 2020-21, following a loss of 703,000 workers between the March and June quarters of calendar 2020.

But given employment in August was already 294k higher than the June quarter average, this means there would be a net rise of just 44,000 over the remainder of the fiscal year. This suggests the government may be expecting net employment losses over the coming months, as JobKeeper and other fiscal support is wound back, before it improves again.

Ultimately, Treasury is not forecasting employment to return to its pre-pandemic level until 2023-24, the final year of the forward estimates.

The $A4 billion JobMaker hiring credit is intended to encourage businesses to hire 16 to 35 year olds on JobSeeker and is expected to “support” 450,000 positions but it is unclear how many of these would be additional.

The Budget also included $A1.2 billion for 50 per cent wage subsidies available for businesses hiring new apprentices and trainees.

The Treasury now expects the unemployment rate to peak at 8 per cent in the fourth quarter before gradually falling to 6.5 per cent by June 2022. But it is not forecast to get “comfortably” back under 6 per cent until 2023-24. This is when the government intends to turn its focus to repairing the fiscal position.

Treasury’s forecasts for wages are in line with the RBA’s but stronger than ANZ Research’s. But with so much spare capacity in the labour market – both unemployment and underemployment – it will be difficult to achieve wages growth of even a modest 1.25 per cent.

The Budget does not materially change ANZ Research’s view on the economic outlook. The spending measures are a little less than expected, particularly on the infrastructure side, but the investment incentives are larger.

Rather than lift public spending further, the Government is clearly endeavouring to engineer a private sector recovery, with particular emphasis on investment. It will mean the mix of growth will be more tilted towards the private sector than previously expected.

Cherelle Murphy is Senior Economist, David Plank is Head of Australian Economics, Felicity Emmett is Senior Economist, and Catherine Birch is Senior Economist at ANZ

This publication is published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia. This publication is intended as thought-leadership material. It is not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in this publication is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in this publication constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of publication. While this publication has been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of this publication or the use of information contained in this publication. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with this publication.