Insight

Education: light beyond the trade war

HAYDEN DIMES, ECONOMIST, BANSI MADHAVANI, ECONOMIST & DAVID PLANK, HEAD OF AUSTRALIAN ECONOMICS, ANZ | JULY 2019

The trade war will weigh on the flow of overseas students into Australia in the short term but growth in standards in emerging nations should prove fruitful for its education-as-a-service sector.

Tourism and education are the primary drivers of service exports in Australia and China is the strongest contributor – at least up until 2019.

Now growth in students and visitors from China has slowed rapidly and ANZ Research thinks uncertainty relating to the trade war is to blame. This is expected to continue into 2020 – when a resolution to the United States-China trade dispute is forecast.

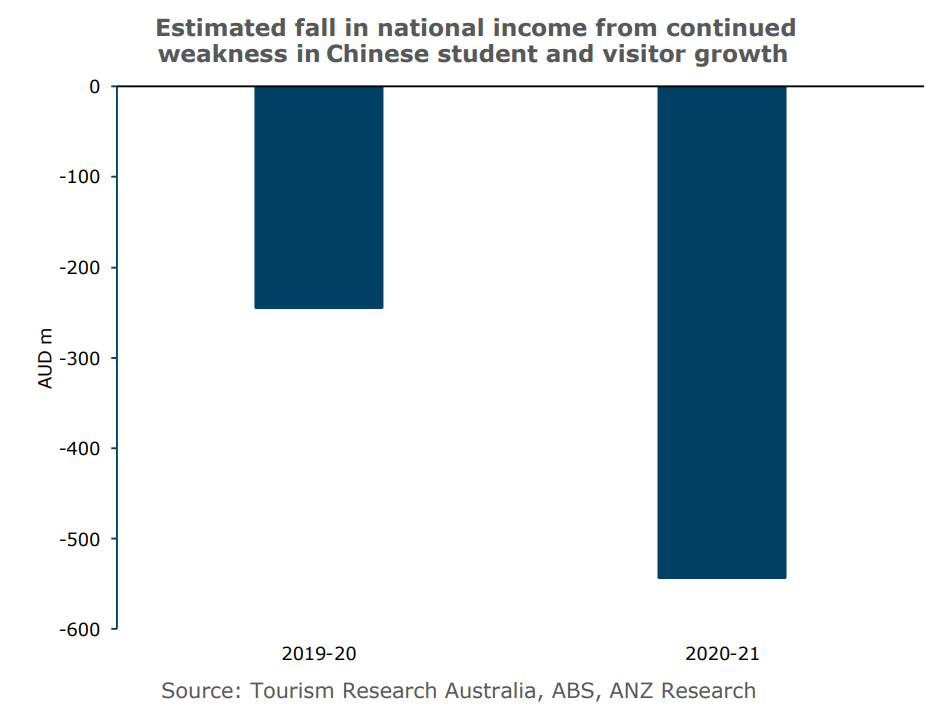

Should further slowing in student and visitor numbers from China indeed play out, ANZ Research expects it will cost the Australian economy around $A800 million over the next two years.

But population growth and increasing wealth in other countries – particularly India and in time, parts of Africa – will provide a growing source of tourists and students for the sector in the long term.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“The trade dispute creates uncertainty, for both visitors and in particular students.”

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

As a service

Service exports have been an important part of Australia’s trade, currently worth around $A8 billion a month. Although resources have long been Australia’s largest export and accounted for a larger share of total exports, services have nevertheless been an important contributor.

In particular, over the last half decade, service exports have been growing at a rate of 13 per cent a year. This is due in part to strong tourism and education-related spending, which has been increasing as a share of Australia’s total service exports.

A lot of the strong growth in tourism and education-related exports has come from increased student and tourism flows from the developing world, particularly China.

This is hardly surprising given China’s population size and rapidly growing middle class over the last two decades.

China now accounts for around 26 per cent of total students coming to Australia and 15 per cent of short-term visitors, the single-largest provider overall.

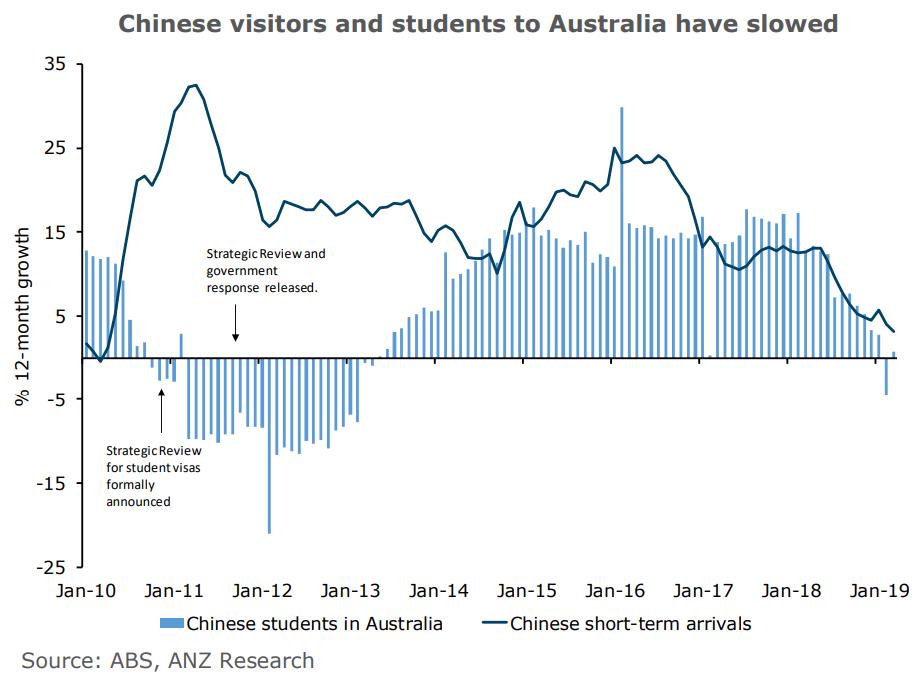

However, since around mid-2018 both student numbers and visitors from China started to slow – a move which has coincided with the escalation of the US-China trade dispute.

As the data is a moving 12-month growth rate, the series are smoothed which potentially explains the delay in drop off (assuming the dispute is the main reason for the slowing).

Uncertain

The trade dispute creates uncertainty, for both visitors and in particular students. When deciding whether or not to study in a country, a potential student is likely to consider possible changes that could impact their immigration status or overall treatment.

In late 2010 the Australian Government commissioned a strategic review of the student visa program. The impact created from the uncertainty about the outcome of the review seemed to have a huge impact on Chinese students coming to Australia. Only once the review and recommendations were finalised did numbers recover.

The notion the trade war is having some impact is further supported by the fact the slowing in Chinese visitors to Australia is not unique.

In early 2019 Chinese visitor arrivals at 20 major global destinations slowed to 6 per cent year-on-year, down from 18 per cent in 2018. Countries like Canada and New Zealand have also seen a slowing down in visitors from China over the same period.

Risks

ANZ Research expects a fall in national income over the next two years if growth in student and visitor numbers from China remains at a similar rate seen over 2019.

In the context of a $A1.7 trillion economy, a potential ‘cost’ of $A800 million is not something which provides huge downside risks for Australia’s economic growth.

Looking forward, there is still plenty of potential for Australia’s education and tourism sectors.

The enormous growth globally of Chinese travellers and students going abroad over last 20 years reflects the rapid expansion of the middle class. The middle class in China is estimated to increase by another 370 million people by 2030.

Although the increase in middle class individuals will allow strong growth in Chinese tourists to Australia to return, ANZ Research does not see quite as much scope for growth in education.

As China continues to develop its universities will also increase in quality and reputation. Once this happens fewer students will choose to travel overseas as they can get the same quality level of education domestically.

The growth in students from the US coming to Australia to study has averaged around 1.3 per cent a year from 2002. Eventually as Chinese universities reach a similar - if not higher – quality, growth will likely be similar.

But there are other markets that will become increasingly important for Australia. This is where the future of the sector is bright.

Hayden Dimes & Bansi Madhavani are Economists and David Plank is Head of Australian Economics at ANZ

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

insight

Everyone is easing: the outlook for Q3

Trade tension has been a surprising drag on growth and central banks could be called into action. Here are ANZ Research’s forecasts for the second half of 2019.

insight

Australia’s options in the trade war

Continued US-China tensions could be a double whammy for Australia’s GDP – and put a dent in hopes for a return to surplus.

insight

Forget the trade war: ageing is China’s biggest threat

The key to China’s future growth will be its productivity and how it handles its demographic challenges.