Insight

Everyone is easing: the outlook for Q3

RICHARD YETSENGA, CHIEF ECONOMIST, ANZ | JULY 2019

Central banks are expected to continue relaxing monetary policy throughout the second half of 2019 as the effects of the trade war persist. In some cases, measures other than lowering cash rates could be an option.

The improved environment ANZ Research expected in 2019 has been set back by the failure of the US and China to reach a trade agreement. The trend to strength in Asian currencies and emerging market equites was largely unwound through May, and bond yields have declined sharply across a broad range of markets.

The trade surprise has been damaging to sentiment but we don’t believe the damage to economic growth is likely to be as substantial. The tariffs that have been announced are still relatively modest and are likely to have had a larger impact on business confidence and investment intentions than on actual activity in the short term.

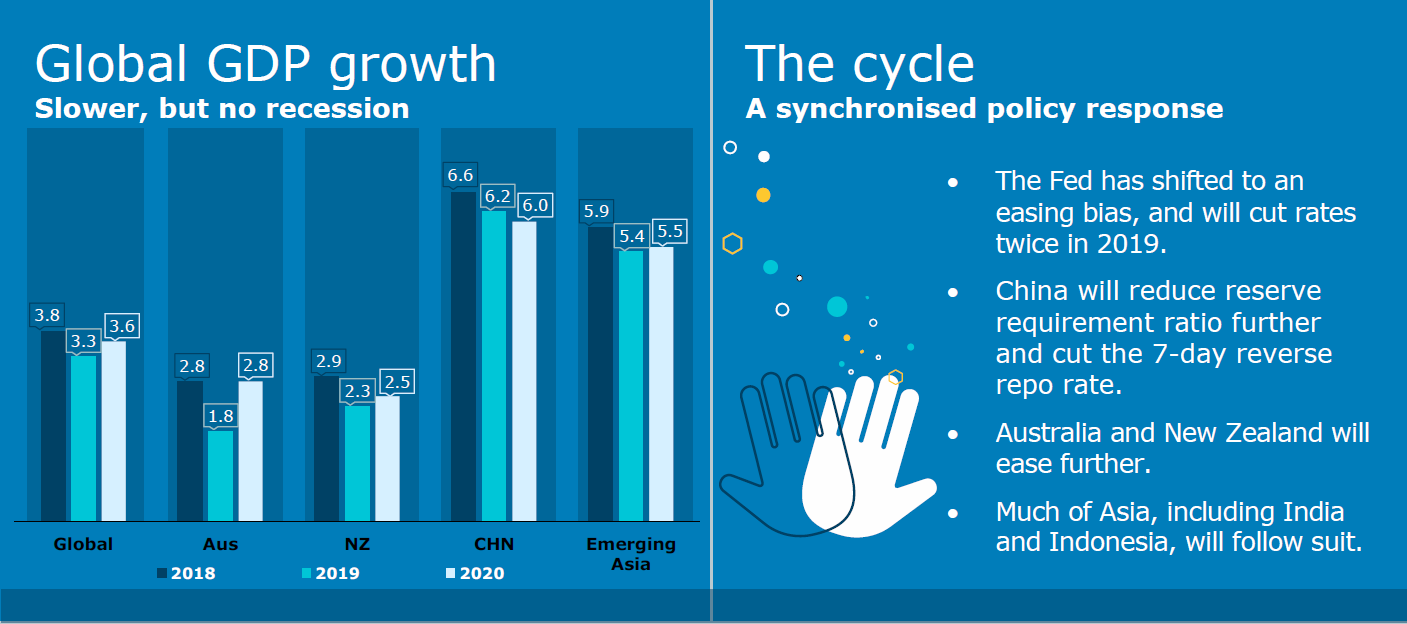

ANZ Research’s GDP forecasts are only modestly changed as a result. Growth expectations in the US, China, India, much of Asia, Australia, and New Zealand have been trimmed. In China growth is forecast at 6.0 per cent in 2020, an important symbolic threshold.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

"The trade surprise has been damaging to sentiment but ANZ RESEARCH DOES NOT believe the damage to economic growth is likely to be as substantial.”

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

While the very flat US yield curve remains a concern, ANZ Research does not expect the US to have a recession if the Federal Reserve eases monetary policy, now also expected. The US business sector does present some points of vulnerability but these are not sufficient to cause a recession without an external driver that surprises the Fed.

The tariff war does hark back to the Smoot Hawley Tariff act of 1931, which is generally held responsible for exacerbating the Great Depression. It is worth highlighting, however, US tax rates were raised sharply during the 1930s in an effort to prevent fiscal deficits. This was the economic orthodoxy of the time.

Additionally, bank deposits and money supply shrank for four years in succession (and by more than 15 per cent in 1932 alone), as monetary policy failed to respond to the depressed conditions. By comparison, during the 2008 crisis US bank lending fell by 5 per cent to 10 per cent for only six months before the US Fed acted aggressively to stabilise conditions.

Four questions for the rest of 2019

Central banks: how will they address the need to shore up monetary conditions and growth?

Easing: will the US yield curve steepen as easing becomes reality?

Trade wars: will tensions continue to impact sentiment?

China: is 6 per cent GDP growth sustainable?

Softer

ANZ Research did not forecast the aggressive decline in bond yields over the past six months, and a significant portion of the decline appears to have been in the inflation component of bond yields. By the same token, there are some good reasons to think that long-term inflation expectations should have declined.

In the US, core inflation has again surprised on the downside over the past half-year after reaching 2.3 per cent in 2018. That level is becoming something of a ceiling based on the post-crisis experience. The Fed’s neutral bias has, as a consequence, given way to an easing bias.

In addition, a range of central banks have eased. This is where the most substantial adjustment in our forecasts has been.

Over the next 18 months we expect:

• the Fed to deliver on its easing bias with 25 basis point rate cuts in the third and fourth quarters;

• China to reduce the seven-day repo rate by five basis points in the second half of 2019;

• a number of other Asian economies to ease; and

• the central banks in Australia and New Zealand to ease close to their floors in cash rates. Alternative forms of easing are possible in both markets before the end of 2020.

In addition, for the ECB we have removed the gradual tightening we had in our forecasts in the second half 2020. As a consequence we expect bond yields to remain very low in the US, China, Australia, and New Zealand.

This ‘everyone is easing’ environment suggests currency markets will remain less uniform than bond and risky asset markets have been. Easing in peripheral markets is typically currency negative. But when the US Fed is easing and global growth is only softening, rather than slowing sharply, risk assets can do better.

ANZ Research’s forecasts embody weakness from the Asian and commodity currencies in the second half of the year, before Fed easing encourages some stabilisation thereafter.

Vigour

While these forecast central bank actions are the proximate driver of bond yields, central banks are only responding to the economic environment. Macro factors must be behind low inflation and the lack of growth vigour.

An insufficient explanation is the decline in inflationary expectations in some countries, including the US and Australia. Certainly the decline will worry central banks. The reality, however, is that inflation expectations have been led lower by inflation disappointing on the downside.

So while lower expectations suggest low inflation is becoming entrenched, it is not the primary driver. There are a range of forces likely playing a role and not all easy to quantify or forecast.

Importantly, the credit side of many economies has been impaired post-crisis. In the US, for instance, the St Louis Fed’s estimate of the velocity of money continued to decline until 2017, and has only risen very modestly since then.

Most central banks give money growth indicators little attention because their relationship with macro variables has not been particularly stable over past decades. This is true. But their replacement, the Philips Curve and related labour market and activity indicators, don’t have as stable a relationship with inflation as was presumed either.

When the provision of credit is impaired, either through global regulation (Basel III), stress tests (the US), or macro-prudential policy (Singapore, South Korea, Australia, NZ and other economies), then in ANZ Research’s view, separately monitoring the money side of the economy has direct policy relevance.

Manifest

Technology also continues to play an important role in the low inflation of recent years, even if quantifying its effect is difficult. This impact can manifest itself directly through a smaller requirement for physical capital, facilitating new entrants into market segments, directly raising price transparency, as well as shifting the mix of demanded skills in the labour market.

One example of the increasing role of technology relates to global trade in services. Services now account for 24 per cent of global trade, a record high. The nature of services trade has also changed fundamentally in recent decades.

Until 1990 travel and transportation accounted for more than half of services trade. That has now fallen to 42 per cent according to the latest data. On current trends, trade in business services is likely to eclipse travel as the largest component of services trade, after passing transport in 2011, with other sectors also growing strongly.

This increased international competition in the services sector substantially broadens the price tension in modern economies beyond agriculture and manufacturing.

Another feature of the landscape – commodities - has a technology component as well. Oil prices are the single largest driver of shifts in headline inflation for advanced economies. In the period before the global financial crisis oil prices had surged between 20 per cent and 50 per cent year on year for long periods. This is a rate consistent with G7 headline inflation of between 2 per cent and 3 per cent.

Since 2012 oil prices have only risen at this rate for two brief occasions – in early 2017 and mid-2018. The shale oil revolution is one of the major reasons oil prices have been subdued post-crisis and is itself a technological advancement.

ANZ Research is forecasting some recovery in oil prices into the end of 2019, and broad stabilisation thereafter.

Richard Yetsenga is Chief Economist at ANZ.

This story is an edited version of an ANZ Research report. To read the full report, click HERE.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

insight

Australia’s options in the trade war

Continued US-China tensions could be a double whammy for Australia’s GDP – and put a dent in hopes for a return to surplus.

insight

Winds of change (and growth) blow in NZ

The indirect impact of the global backdrop – anxiety over the outlook – may for now be bigger than the direct one in NZ.

insight

Forget the trade war: ageing is China’s biggest threat

The key to China’s future growth will be its productivity and how it handles its demographic challenges.