Tenth

Over a tenth - 12.6 per cent - of China’s population is now above 65. Japan faced a similar situation in 1990, but China’s 2019 GDP per capita is only about 37 per cent of what Japan’s was then.

With quantity of labour is no longer a selling point for China, other solutions are needed. First, innovation will increase China’s multifactor productivity to offset the negative impact of a shrinking working age population. Second, urbanisation will improve income and hence consumption.

Urbanisation can also address the urban-rural income disparity. In 2019, disposable income per capita of rural households was 16,000 yuan, only 37.8 per cent of the income of urban households.

Between 2006 and 2018, the number of Chinese cities of a million people grew from 117 to 161. In 2018, 73 per cent of urban population growth came from 30 metropolitan areas, in which 70 per cent originated from the outer zones of the cities.

This development will continue to drive China’s urbanisation rate. At present, that rate is 60.6 per cent, 15 percentage points lower than the level of Japan in 1980.

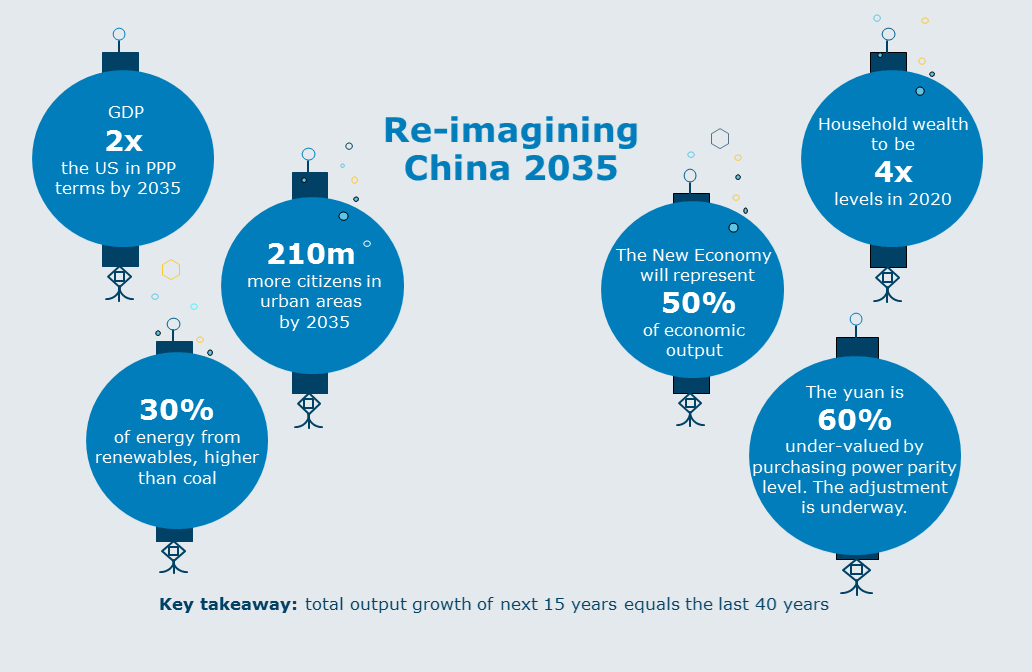

As China increases its urbanisation rate by 1 percentage point annually, it will urbanise additional 210 million people and double the average income per capita by 2035.

Shift

China’s economic rebalancing is often interpreted as a shift towards a consumption and service-led economy, with manufacturing and investment declining. However, China has never lost sight of manufacturing.

The hollowing out of the industrial base in Japan and the US has provided a vivid lesson for China. The trade tensions with the US and high competition in the global tech sector have further urged China to secure its manufacturing sector, especially in the high value-added segment.

This is the foundation of the real economy, noted in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan. A stable manufacturing sector will prevent economic growth from sliding dramatically, especially when the sector’s productivity is lifted.

China’s vision for 2035 suggests investment will remain relevant. City clustering plans will play a major role in facilitating urbanisation. Land reforms will fundamentally change the property landscape.

The next 15 years will see the formation of several city clusters. Population will start to move away from several mega cities. Peripheral cities will be connected via a highly efficient transport network. The goal is to develop ‘one-hour life circle’ routes.

Fifteen years ago, China began to plan for its high speed rail project. Today, the network has covers 36,000 kilometres in total. As the country urbanises, the HSR will also double to 70,000 kilometres.

New

China’s “Three New Economies” (三新经济) refers to new industry, new types of businesses and new business models, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Besides digital-based sectors, new energy vehicles (NEV), healthcare services, express delivery services, long-term apartment leasing, customised dining, eco-tourism and comprehensive business management are all recognised.

Lifting multifactor productivity is one way to offset the negative impact from a diminishing working age population According to IMF research, a 1 percentage point increase in the digitisation of China’s economy brings about a 0.3 percentage point increase in GDP growth, with a two-year lag.

Digitisation brings lower transaction costs, decreased information asymmetry and enhanced production efficiency.

Changing energy demands are a key factor. China’s new energy revolution involves a combination of three long-term objectives: decarbonisation, industrial upgrade and energy safety.

China has established targets in adherence with the Paris Agreement, including a 20 per cent share of non-fossil energy in total energy consumption, a 60 per cent to 65 per cent reduction of carbon intensity compared to 2005, and to peak its carbon emissions before 2030. China has announced to target zero net emission before 2060.

To achieve these goals, China will likely meet the bulk of its new energy demand with renewables during the 14th five-year plan period. The shift to new energy sources will help China’s industrial upgrade.

The supply side will benefit from renewable energy capacity investment, while electrification will accelerate technological progress in manufacturing. The economy will also benefit from the cost efficiency of new energy.

ANZ Research estimates China will add 800 gigawatts of new renewables capacity, or 4 trillion in investment, based on 2019 global benchmark capital cost per megawatt during the 14th five-year plan. Along with other plans, these will add at least 1.8 percentage points to annual growth in the next five years.

Within the national security framework, energy safety is a growing concern and received a special mention in the 14th five-year plan. The development of renewables will help China reduce its reliance on imported fossil energy, which is easily affected by rising geopolitical risks.

In 2019, China’s energy self-sufficiency rate was 81.5 per cent. China has set a goal of 95 per cent by 2050, meaning China will by then be able to supply its own domestic energy demands.

Earn

China’s wealth increased at an average pace of 17.7 per cent in 2001-2016, 4.2 percentage points higher than nominal GDP growth. If this trend is maintained in the next 15 years, the national wealth in 2035 will be four times that in 2020, making China the world’s largest wealth market.

China’s growth will be around 5 per cent in the next 15 years, higher than developed economies. The RMB will gradually appreciate as productivity increases, as implied by the Balassa-Samuelson Effect. China’s assets will be revaluated and financial wealth of China will rise.

Comprehensive financial reform will be necessary to deepen China’s securitisation in the next 15 years. The market-based interest rates and exchange rates remain at the core of that reform. The continued opening-up of the financial markets, as stated in the 14th five-year plan, will be helpful.

If Milton Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis is any guide, China’s national wealth is where the purchasing power of Chinese shoppers comes from. Some economists may overlook the implications of Friedman’s theory, but it is hard to look past the Chinese crowds on the Avenue des Champs-Elysees.

Raymond Yeung is Chief Economist, Greater China at ANZ

This story is an edited version of an ANZ Research report. You can access the original report HERE.