INSIGHT

India Rises On Its Own Terms

Download the PDF

________

India is leveraging demographics and policy to grow in a world very different from when China began to rise: the eve of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Complicated and awkward reform, slower growth and a structurally impaired banking system again seem to be tarnishing India’s potential. Too often however, rather than being considered on its merits, India’s performance is compared with those who went before it. Klaus Schwab’s Fourth Industrial Revolution framework–characterised by the joining of physical production to increasingly sophisticated digital technologies–is a useful way to consider global growth opportunities in the decades ahead rather than the decades that have passed. Its emphasis on the connection between the physical and digital offers a new perspective on how a country’s fundamentals come to a sum greater than its parts. Looking at India through this lens reveals a unique set of opportunities, spanning not just the production of goods and services but also serving a consumer base, for in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, these sectors intertwine more tightly than ever before.

No China repeat: size is about the only commonality

This growth will take place in a world very different from how it was at the turn of the millennium when China joined the World Trade Organization. Technological progress and China’s success have fundamentally changed the game and should rule out the kind of comparisons that have tempted observers since India’s economic growth began to outpace China’s in 2015.

In the ‘elephant versus dragon’ race, size (specifically population size) is one of the few commonalities that make comparison between these two countries reasonable, so great are their differences. Today, India’s economy is one-fifth that of China’s. In both nominal aggregate and per capita GDP terms, India’s economy today is the same size as China’s was a decade ago. Even assuming that 2017 is an outlier and India grows faster than China in the decade ahead, its rise will not be a simple catch-up story with India becoming the next China. Though it will not rise on the same scale as China, India’s size still means the opportunities in this next phase of growth will be significant.

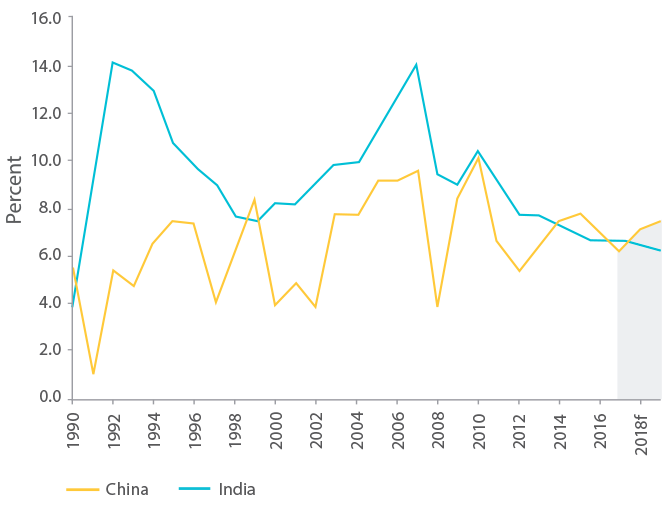

FIGURE 1:

GDP growth in annual percentage

Source: IMF, ANZ Research

Divergent fundamentals

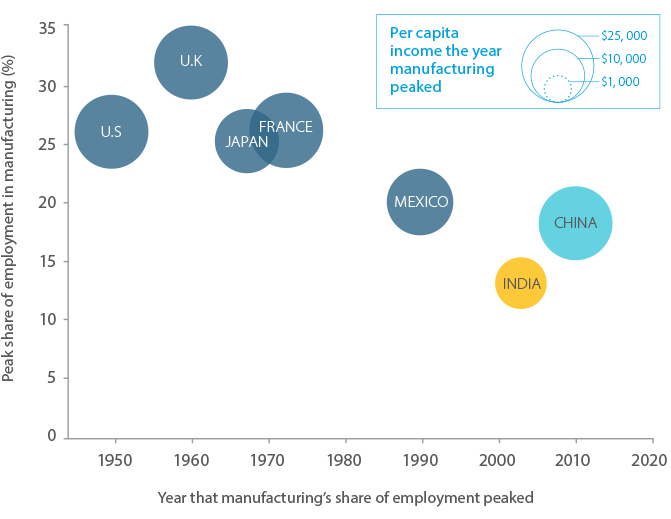

Today, Chinese manufacturing labour costs nearly four times as much as it does in India and China’s working-age population is projected to drop below India’s in a little over five years. Despite this, and even with India’s renewed policy commitment to industrial strategy with ‘Make in India’, the manufacturing-paved path to growth is much more challenging than it used to be.

We’ve written before about how radically less labour-intensive manufacturing has become since the early 1980s, when China opened its doors to foreign investment. There is even an argument, developed by Dani Rodrik, that several developing economies have reached a state of “premature deindustrialization” without having undergone a typical industrialisation cycle. In Asia, South America and Africa, there is evidence that manufacturing’s share of employment is peaking before it can deliver either high wages or broad employment. At the same time, compelling research from the United Nations argues that this ‘average effect’ is accounted for by a narrow group of countries (including China) dominating global manufacturing. The overall message however, is that the manufacturing-led path to economic development is less open than it used to be.

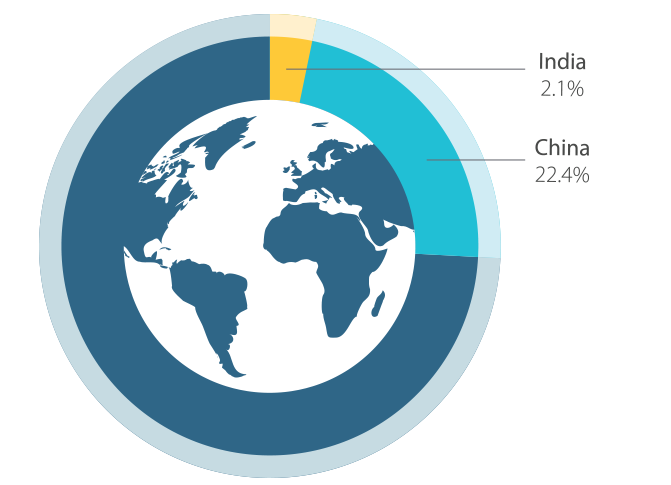

FIGURE 2:

World manufacturing in 2012

Source: Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation (MAPI), & United Nations.

That does not mean that manufacturing cannot grow in India. In fact, manufacturing grew 10.8% in 2015-16 and 7.9% in 2016-17. Smart reforms such as the ‘Make in India’ policy along with recent achievements including FDI and labour law simplification, infrastructure investments and power sector reforms are targeting areas in which India has needed to make up ground. India ranks 130/190 on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rankings (China is at 78 and Taiwan at 11). India is at 79/176 on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (China has the same rank). On average it takes 30 days to set up a business in India; and most entrepreneurs reel under tax burdens, something that the government has tried to address through Goods and Services Tax (GST) reforms.

All of this is evidence that India’s manufacturing potential should be taken seriously. India’s rise in the latest Global Competitiveness Index is notable. In fact, when you compare India and China at similar stages of development, India is outperforming on a number of measures. Manufacturing will not provide the broad base of economic growth that it did in China, primarily because it is becoming less labour intensive globally. Yet, it can still grow in India provided progress on labour and infrastructure reform continues. That matters because manufacturing enhances India’s other strengths and the interplay between these factors is the key to India’s edge.

In fact, there is a simpler argument to be made. Namely that India is operating with such a range of inefficiencies that addressing these over time should naturally bring some growth in the economy. Consider that in recent years energy price subsidies have been almost entirely abolished, the monetary policy regime has changed fundamentally, large parts of the informal sector have integrated into the mainstream economy, a GST is in place and the banking sector is recognising and dealing with non-performing assets. All this has cost economic growth, particularly as the banking sector adjusts to much greater transparency about the value of its assets, but it implies that we can be much more confident about the base on which India’s growth is built; particularly as we consider China’s trajectory over coming years.

Where India really shines

India’s service sector continues to outperform China’s service sector and offers large potential for continued economic growth. It contributed 54% to the gross value added (GVA) in FY 2017 and is expected to grow at 8.5% in FY 2018, making it the fastest growing service sector globally. The IT sector is expected to reach annual revenue of USD350 billion by 2025 (Perspective 2025: Shaping the Digital Revolution) and India’s start-up system continues to expand and break into new territory.

Taken with India’s steps forward in manufacturing, the country’s potential starts to come into view. In June, Harvard Kennedy School’s Center for International Development (CID) released the latest edition of its Atlas of Economic Complexity, with growth predictions updated to 2025. CID Director and lead researcher Ricardo Hausmann commented; “India, Indonesia, and Vietnam have accumulated new capabilities that allow for more diverse and more complex production that predicts faster growth in the coming years.” The report calls out the strides India has made in economic complexity, saying “India has made inroads in diversifying its export base to include more complex sectors, such as chemicals, vehicles, and certain electronics.”

This increasing economic complexity presents a great opportunity in the form of connecting India’s traditional IT expertise to its newfound gains in manufacturing capabilities. Noting that manufacturing industries that are near their markets and supply chains tend to create long-term employment, the McKinsey Global Institute observed that “with India’s strong domestic IT capabilities, which are increasingly relevant in manufacturing, firms operating in the country can reach customers more effectively, streamline manufacturing processes, and create more efficient supply chains.” PwC suggests that for the hypercompetitive chemicals industry such efficiency may be vital to company survival, noting that integrating digital systems can reduce operating costs by 2-10% and capture gains of up to 25% in capacity utilisation.

The development of tacit productive knowledge (a.k.a. know-how) is critical to economic growth. With regard to harnessing global knowledge India has an ace in the hole: its diaspora. At about 16 million, the Indian diaspora is the largest in the world. Already, its remittances account for a stunning 3.4% of India’s GDP and its members frequently serve as ‘angel investors’ to domestic start-ups. Earlier this year the Modi government took steps to leverage this human capital with changes to Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) cards. The recent changes seek to facilitate further participation by overseas Indians in the economic and intellectual life back home; and it allows them to work in India for short or long periods and to own property, while retaining their citizenship of other countries. The large number of English speakers in India would seem to be a significant source of strength in an increasingly service-driven world.

The domestic market

Within India, advances in cities, on gender inclusion and in the digital economy are strengthening the dynamics of production and consumption locally and may be the start of bigger trends still; if the active reform program of the past 18 months has cost growth in the short term.

Homi Kharas at the Brookings Institution estimates that in the next decade the world will reach a tipping point where the middle class will be, for the first time ever, the largest income segment. A majority (88%) of these new billion entrants will live in Asia, leading to big distributional market shifts in favour of both India and China. India is projected to be the third largest consumer economy by 2025, with consumption tripling to USD4 trillion (BCG). In AT Kearney’s Global Retail Development Index 2017, India is ranked first for “its growing middle class and rapidly increasing consumer spending.” Growth of metropolitan city clusters, almost 50 of them, creates densely populated urban and semi-urban consumer bases and will drive 77% of the country’s GDP (McKinsey).

And there is still greater potential to be tapped. As the McKinsey Global Institute noted in 2015, only 17% of the country’s GDP was generated by women; in China, that number was 41%. According to the most recent World Bank data women make up just 27% of India’s workforce, compared to 63% in China and the global average of 49.5%. A host of factors including social prejudice and discrimination have led to this statistic. Over the past decade, important progress has been made: the gap between girls and boys at primary and secondary schools has been eliminated. Efforts are underway to sustain and advance progress on gender equity, from the central government’s ‘Save the Girl Child’ policy, to the work of NGOs and state governments. In June, the United Nations awarded first prize for Public Service to West Bengal for its policy of offering cash transfers to retain girls in school.

Yet there remains a great deal to be done. Last year the World Economic Forum noted firstly some regression on women’s estimated earned income, and secondly that India “continues to rank third-lowest in the world on Health and Survival, remaining the world’s least-improved country on this subindex over the past decade.” McKinsey estimates that bringing 68 million women into the economy could lead to an incremental increase of GDP of 1.4%. We’ve emphasised previously that if labour force participation were to become equal globally, India and Indonesia would benefit the most in terms of added economic growth. The extent of India’s rise will in no small part be decided by its success in this regard.

Technology and fiscal policy reforms are also boosting consumption opportunities. In its report, BCG observed that India’s online consumers grew seven-fold in the last few years (to between 80 and 90 million) delivering USD45-50 billion in the decade to 2025. Innovations in the consumer finance sector are overcoming barriers to broader online consumption.

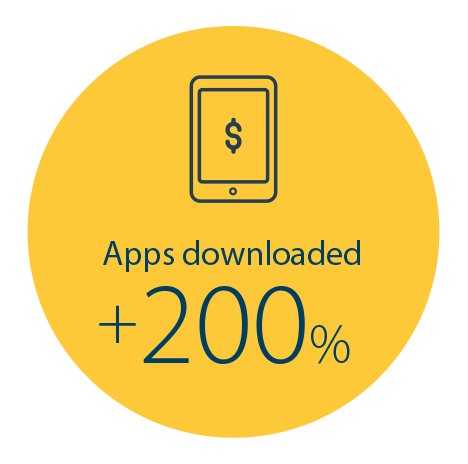

Paytm, India’s largest mobile money operator, backed by the Chinese Alibaba Group, was the single largest beneficiary of the demonetisation program of the government in November 2016. By January 2017 Paytm’s traffic increased by 435%, app downloads by 200% and transactions by 250%. That translated to 80 million active users, still less than a quarter of Alipay’s 450 million, but the biggest reach in South Asia. Already, Alibaba and Amazon are at war for domination of India’s eCommerce market and only in July Amazon announced an additional USD250 million investment.

FIGURE 5:

Paytm post demonetisation

Increase from Nov 2016 as at Jan 2017

Source: Hindustani Times

With mobile phones ubiquitous and increased penetration of low-cost smartphones, the opportunities are significant. At USD6 a month for a mobile phone plan with 1Gb of data on a 4G network, mobile access in India is incredibly cost effective. Reflecting the penetration that results from this sort of access, Prime Minister Modi presents a very progressive digital footprint through his own app. This has affected (and indeed reflects) the broader support base that the BJP government has developed by harnessing a level of Bharat support that is traditionally Congress in its allegiance. Bharat is the original Hindi word for India, now more colloquially used to refer to non-urban voters.

Data leads the way to opportunities still unseen

In addition to public cloud services, the other features of this sophisticated digital ecosystem include a billion-strong Unique Identity Database (UID) and an aggregator of digital systems that connects consumers with retailers and financial service providers– India Stack. Consumers can unlock digital ‘lockers’ containing their user data to pay for products at a local grocery store or a cab ride, receive welfare benefits or send money to relatives. Merchants and banks can use India Stack to verify users by linking into the UID, thereby fulfilling the cumbersome ‘know your customer’ requirements.

In the next few years the Indian internet service market is likely to grow, further leveraging this digital ecosystem and the ‘new’ hundred-million consumers who enter the lower middle class segment. Innovative partnerships in this sector are already mushrooming. For example, the messaging application WhatsApp is currently designing a payment architecture with the State Bank of India, National Payments Corporation of India and other financial institutions. Gartner projects that the public cloud services market in India will grow to USD1.8 billion in 2017. In May, Oracle validated its Oracle Cloud Platform to develop applications using India Stack services. Cloud infrastructure of this kind will help businesses store and analyse consumer digital data to develop new products and services.

The rules of growth have changed: India has adjusted its game plan accordingly

Technological change and China’s enduring industrial dominance suggest that the textbook path from farm to factory to office may well be a development dynamic relegated to the history books. For today’s emerging economies, technological progress is no longer an automatic means by which a rural, impoverished population can rapidly attain middle class prosperity. However, technology has added opportunities for growth in the services sector, boosted the ease with which vast segments of a country’s poorest can begin saving and spending, and even created a basis for entirely new industries. India appears to have the favourable conditions and policy commitment to make significant progress in this new game of growth.

India benefits from a youthful population, a heritage of service sector strength, a skilled and wealthy diaspora that is the largest in the world and electronic payment systems that are rapidly developing to serve its tremendous domestic market. The relative political stability of India and the strength of the Modi government to continue to make reforms are a source of optimism for the short-to-medium term. The broad agenda of policy initiatives, the push to harness the talents of the diaspora and the efforts to include more women in its workforce and consumer base target the opportunities in the new game of growth and are poised to continue.

Should they succeed, the elephant will not become a copycat dragon. Rather, India will have written a growth story on its own distinctly 21st century terms.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

research

Demographic Time Bomb? Time to Question Conventional Wisdom

Ageing populations combined with rising automation have conventionally been omens of economic slowdown. Here are 5 reasons not to panic.

insight

Why Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs) Will Need To Fuel Asia’s Growth

Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) are well-placed to fill the Asia funding gap.

insight

Coming soon — NPP, a Game-Changer for Australian Financial Institutions?

A guide to how Australia’s anticipated New Payments Platform will benefit banks and insurance companies.