RESEARCH

Demographic Time Bomb? Time to Question Conventional Wisdom

Download the PDF

Richard Yetsenga, Chief Economist, ANZ | June, 2017

________

Today’s ageing demographic profile may not necessarily lead to slower growth or secular stagnation; even though that now seems to be the conventional wisdom. A range of factors have led to reduced trend economic growth in many economies over the past decade, but in our view demographics is one of the least worrying. We question the consensus, and while there are policy challenges, particularly in an environment of sceptical globalisation, the future might well be less aged than you think.

Five reasons for optimism

The global population is ageing, with life expectancy rising and fertility rates declining. This is happening in both developed and emerging countries. Asia’s elderly population is projected to reach nearly 923 million by the middle of this century1, and last October Australia’s life expectancy hit an all-time high of 84.5 years for females and 80.4 for males. In one sense this is good news as it reflects the fact people are enjoying longer lives.

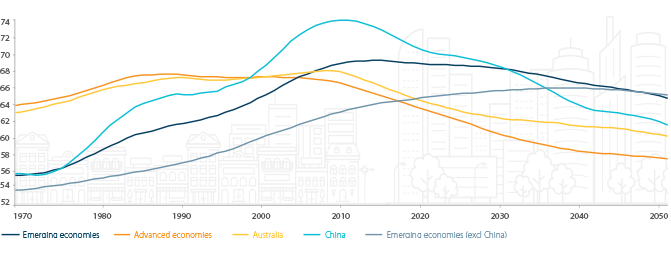

With people also having fewer children, longer lifespans mean the ‘old age dependency ratio’ – those aged above 65 years (currently defined as ‘old age’) as a share of those between 15 and 64 years (‘working age’) – has steadily grown. In the current decade, for most countries and regions, the working age population as a share of total population will pass its peak (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Demographics—passed the peak

Working age population as a % of total population over time

Source: United Nations, ANZ Research

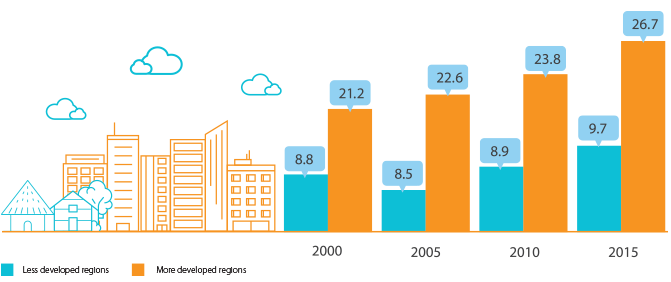

Old-age dependency ratio

(Ratio of population aged 65+ per 100 persons of working age 15-64)

Old-age dependency ratio (selected Asian/APAC countries)

CAUSE FOR CONCERN OR CELEBRATION?

Conventional wisdom claims this is a problem. As a population ages, it is assumed there will be more ‘unproductive’ people (retirees) in the economy, supported by diminishing numbers of working people, leading to unsustainable pensions and buckling health care costs. However, there are some good reasons to question this conclusion.

1. Demographic predictions can be wrong. It wouldn’t be the first time.

Demographic trends are not easy to forecast, despite the apparent smoothness and linearity in the trends we see, and things we now assume to be norms can easily become surprises. For instance, the fall in birth rates from the 1970s was not anticipated or expected3. The US Census predicted 40-49 million births for the 1970s, but in the end, there were around 33 million. The idea that the number of births would fall below the replacement rate (ie two per couple) was virtually inconceivable. Several factors led to this confounding of expectations, including a rising age of marriage, greater deferment of childbearing, and wider access to birth control.

2. Trends aren’t static, they’re responsive.

While demographic trends can appear to be linear, that doesn’t preclude adjustment. Sociological and technological changes shape future demographic trends and affect economic outcomes.

As US Federal Reserve Chair, Janet Yellen conveyed in remarks in May 2017, the last 125 years of US history offer numerous examples of the economic upside generated by shifts in participation. In 1890, only 54% of females aged 5 to 19 were enrolled in school; and of the 2% of all 18-24 year olds who were enrolled in an institution of higher learning, only one third were women. The latter half of the twentieth century provides a clear contrast: between 1948 and 1990, the rise in female participation contributed about 1/2 percentage point per year to the potential growth rate of GDP.

Today, there are some hopeful signs of progress, sometimes in unexpected places. Female labour force participation is now higher in Japan than the US, for example. Yet it’s also clear that there’s great potential that remains untapped. As Ivanka Trump and Jim Yong Kim recently noted only 55% of women participate in the paid workforce globally, depriving the world of billions of dollars of economic activity each year. We’ve argued previously that in Asia, such a renewed push could create a second ‘demographic dividend’ just by enabling women to work in greater numbers, adding 314m employees to the labour force in the region.

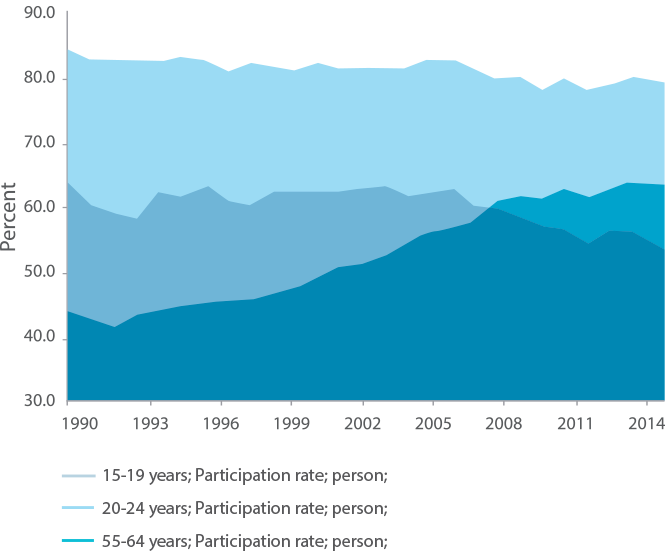

Those who might fret that such incremental change is too small to be of consequence, should also consider that diverse and unplanned societal shifts can provide grist for government policy changes that in turn further hasten change, in a kind of reinforcing feedback loop. In Japan, a corporate culture that traditionally forced employees out at age 60 gave way to contemporary realities in 2013, when legislation was enacted requiring companies to keep on all workers who wish to continue working until 65. The country is working to gradually raise the retirement age from 60 to 65. In Australia, the participation rate of those aged over 65 has doubled in the last 15 years, and discussions are under way to gradually raise the retirement age to 70. In Brazil efforts are in place to raise the retirement age from the 50’s, to 65. We could go on.

3. Technological innovation is challenging workforce assumptions

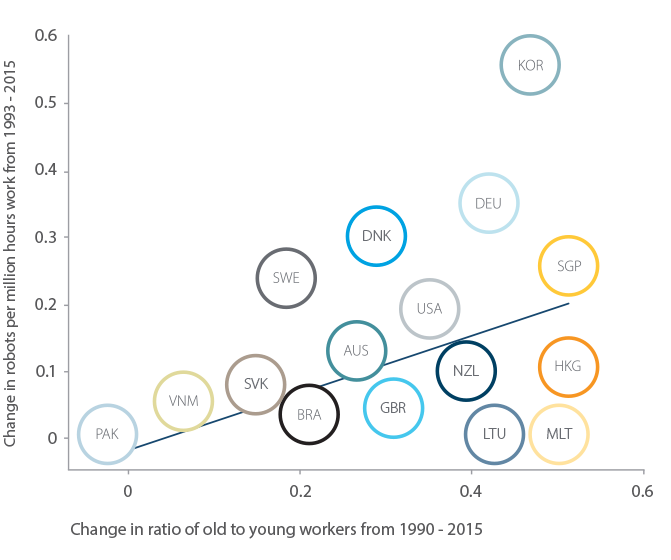

According to a recent paper, Secular stagnation? The effect of aging on economic growth in the age of automation, the big story here may already be underway. Surveying OECD data, the authors demonstrate that countries with ageing populations are likely at the forefront of adopting robots. They suggest that, where capital is abundant and cheap labour scarce, technology can fill the gap and even lead to higher economic growth.

FIGURE 3

Effect of ageing on economic growth in the age of automation

There have also been subtler technological changes in the last few years that invert the assumption that ageing must equal vanishing productivity. A study by Harvard Business Review on working from home found that older workers were most likely to benefit, as they have established commitments outside the workplace. In contrast, the social lives of younger workers are more closely tied to their workplace (and they may need closer mentoring and direction).

Making productivity less contingent on physical presence may hold promise for ageing white-collar workers but that may be a bit trickier for those whose work can’t be so neatly divided from bodily health. Plumbers, assemblers and roofers depend on capabilities that decline with age - flexibility, reaction time and balance - to do their jobs. It’s unrealistic to suggest they can simply be re-trained into IT workers once they age out of manual labour. And yet, precisely because that issue seems intractable, we need to think about it now by looking at what we can learn from programs that provide opportunities for retraining.

Singapore’s SkillsFuture program provides an interesting pilot program for Asia Pacific. It was introduced last year and offers Singaporeans a $500 credit toward skills courses of their choosing. One year in, older workers stand out from other demographic groups because of their preference for information and technology courses. This shows that given the opportunity, older workers can adapt to the technologically-driven demands of the current labour market. Close attention should be paid to see how we can use such programs to the broadest effect. Once again, far from being a phenomenon against which policymakers are helpless, demographic change is a manageable one—indeed there are already real-world policy experiments to examine and build on.

4. Young people are ahead of the game.

The falling participation rate for young people actually carries a silver lining. It indicates that young people are taking time to study to meet the increasingly sophisticated requirements of the labour market. In fact education is, in many ways, the way that we have always stayed ahead of machines.

In Australia last year, youth participation in full-time education rose to a record high (52.44%). The proportion of workers in Australia who hold a bachelor’s degree or higher rose from 23% in 2005 to 31% in 2015 and the unemployment rate for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher was 3.4% versus 7.7% for those with only Year 12 education. More recently, this progression has continued with double-degrees (rather than single-discipline degrees) increasingly the norm. Last year, in our Servicing Australia Report, we wrote that the country is transitioning to a new set of drivers that will make the service sector an even larger share of the economy by 2030 than it is today and will create an even greater demand for skilled workers.

Indeed, in this transition, education will benefit both individual workers and the economy as a whole. Equipping workers with the capacity to make sophisticated judgment calls and think creatively will enable them to secure jobs as more routinised tasks are automated, and these new jobs have the potential to be more stimulating and fulfilling. Moreover, consumption by better-paid workers could help to offset some of the drop in spending that would result from any population decreases. While we noted that the increased demand for education will require the government to work harder to ensure funding—possibly in concert with the private sector—this is another reminder that demographic change is manageable. By spending more time in school, young people have already indicated a mechanism for doing so.

5. Immigration

The final factor that affects how economies ‘age’ is immigration, and potentially the movement of people from poorer countries with younger populations to wealthier countries with ageing populations. The economist Branko Milanovic recently explored how global income inequality in 1870 depended two-thirds on a person’s class and one-third on their location, whereas today that figure has nearly flipped. Today more than 50% of a person’s income is determined by where they live.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The economist, Branko Milanovic, recently explored how global income inequality in 1870 depended two-thirds on a person’s class and one-third on their location, whereas today that figure has nearly flipped. Today more than 50% of a person’s income is determined by where they live.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Beyond benefitting immigrants and alleviating global poverty, migration can address the economic challenges of wealthy host countries’ ageing populations in ways both obvious and subtle. The most obvious sees not only a boost to the number of working people, but an increase in the younger portion of the population. This is because migrants are often young and they are also likely to have their own families in time. For instance, a modest temporary increase of immigration to Japan, of 4 people per 1,000 inhabitants over the course of 2020 and 2029, would see the number of live births be six percentage points higher by 20604.

Little surprise then that to keep the working age (15-64) population constant by 2050, the UN forecasts that countries will need to ‘import’ many millions of migrants5. Indeed, today many of the smaller, open economies in Asia Pacific do this to some extent or another, including Singapore, Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand.

The way that they do also highlights that immigration is more than just about ‘replacing’ people. It is about injecting ideas and expertise to strategically boost sectors that are vital to a country’s future. That’s evident in Singapore, where immigration is part of kick-starting areas like biomedical sciences, digital animation, and aerospace.

None of this is to discount the political realities of migration, particularly in advanced economies, given the more sceptical phase of globalisation in which we find ourselves. Yet as the victory of Emmanuel Macron over the anti-immigration Marine Le Pen in the presidential election in France reminds us, anti-immigration outlooks aren’t fated to carry the day. With bold, creative, and compelling arguments, forward movement is possible.

For example, the counterintuitive case can be made that increasing immigration is the best way to ensure the future looks something like the past—keeping pensions financed so today’s workers will enjoy retirement benefits similar to previous generations, as The Economist recently argued. Singapore’s policy suggests another approach: a hopeful message about gaining a new competitive edge in the global economy. The best way to escape ‘us v them’ politics is to convincingly illustrate how immigration is a vital ingredient for a future of shared greater prosperity.

THE WORLD IS CHANGING. DON'T LOSE SIGHT OF THE UPSIDE.

And that brings us back to the big picture. There are a range of factors which may have reduced trend economic growth in many economies over the past decade, but in our view demographics is one of the least worrying. We should not assume that today’s ageing demographic profile necessarily leads to slower growth or economic problems. While many investors, businesses, and financial markets now presume that this is the case, it’s time to think more critically about this issue.

There are plenty of reasons to question conventional wisdom and the definitions of the ‘working age’ population’. Indeed, when Germany’s Otto von Bismarck first introduced pensions for workers over 70 more than a century ago, life expectancy was just 45!

There seems little doubt that scientific and sociological forces influence a country’s demographic and economic trajectory. Countries have powerful tools at their disposal – including education, pension and migration policy – to influence outcomes. The future might well be less aged than you think.

1 https://www.adb.org/features/asia-s-growing-elderly-population-adb-s-take

2 https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/

3 http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/17957/1/ar850003.pdf

5 http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/ReplMigED/ExecSumnew.pdf

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

research

Retail’s Newest Innovation: Deflation

The long-trend of commoditisation has re-shaped the dynamics of competition in many markets. Innovations in retail suggest the downward pressure on prices has much further to run and industry deflation will continue. Welcome to Alid-isation.

research

2017: Globalisation in the rear-view

Calls to restore a 20th-century industrial economy will create openings for intra-Asian regional consolidation and digital dominance for China.

research

The Paradox of 50/50 Politics

Conventional thinking says a backlash against globalisation is behind the biggest political upsets of 2016—but what if the issue is that the world no longer conforms to our predictive models? By giving voice to those previously without one, social media may have changed things more fundamentally.