RESEARCH

The paradox of 50/50 politics

Download the PDF

By Richard Yetsenga, Chief Economist, ANZ | November, 2016

________

Conventional thinking says a backlash against globalisation is behind the biggest political upsets of 2016—but what if the issue is that the world no longer conforms to our predictive models? By giving voice to those previously without one, social media may have changed things more fundamentally.

July’s week of waiting on the outcome of the Australian federal election is part of a new global pattern: major political events where the best predictions don’t offer much to bank on. These surprises have not just been in the US, UK or Australia, but also as far afield as Columbia and Hungary.

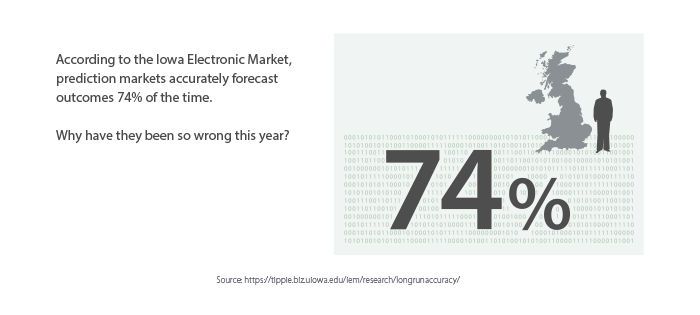

Prediction markets have enjoyed a long run of accurately forecasting the outcome of elections.

Researchers at the Iowa Electronic Market (IEM)—the standard-bearer of election markets in the United States—find that prediction markets accurately forecast the outcome of national elections 74% of the time. Yet for two of the most notable international political events of 2016—Brexit and the ascent of Donald Trump—prediction markets have been wrong.

In the Brexit referendum, prediction markets suggested a 75% likelihood that Remain would win. And, as American Enterprise Institute blogger James Pethokoukis observed in December 2015, betting markets continued to peg Marco Rubio as the front runner for the Republican nomination even at that late date, although Rubio had been trailing Trump in national polling for months. And, even in late September of this year, national polls suggested there was little to separate Trump and Hillary Clinton. Only more recently has a gap opened.

Has something changed, rendering sophisticated prediction models only as good as a coin toss? Yes, something has changed, but not what you’d expect.

Time to turn the spotlight on what went unseen

Trying to explain the discrepancy between betting markets and US polls back in December, Pethokoukis suggested that the thought of Trump as nominee was ‘may be just … unthinkable’ to the educated class. (And, indeed, Pethokoukis was hardly alone; no less than the famous American statistician Nate Silver put Trump’s chances in the low double digits as late as January of this year, a fact which he later attributed to prioritising educated guesses above updated modelling). But what does that mean, except that the ‘smart money’ didn’t try to seriously think through why it might be possible? Today, we risk making the same mistake if we don’t look closely at what the data are telling us.

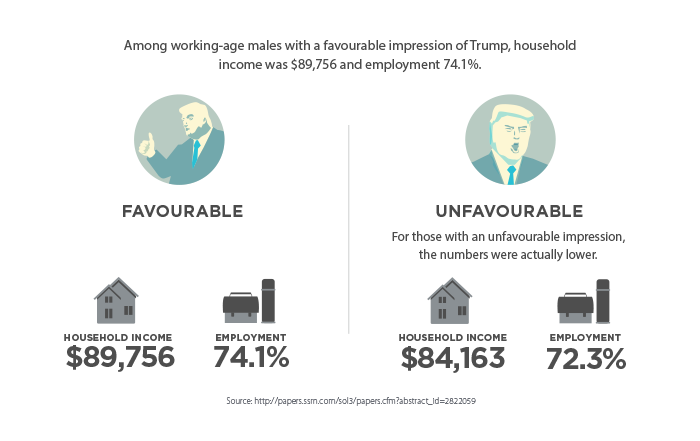

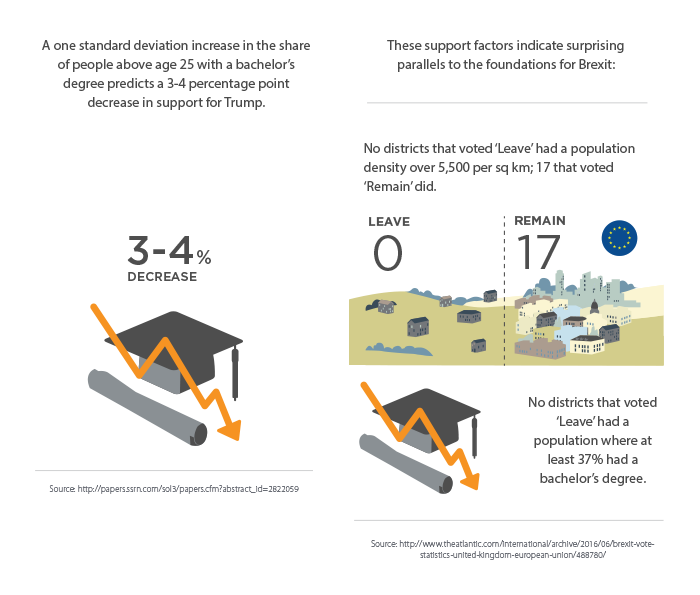

A recent working paper by Jonathan Rothwell, senior economist at Gallup Polling offers some interesting insights -- ‘Explaining nationalist political views: The case of Donald Trump’, highlights the fallacy of the conventional thought process which links Trump’s appeal to economic anxiety surrounding globalisation, This piece argues that the data do not support this view. For example, regions more exposed to Chinese manufacturing imports actually show less Trump support, not more, and Trump supporters are actually just as wealthy as those who oppose him. Rothwell finds that, despite what seems to be the conventional view, competition from migrant labour or the decline of factory work are inadequate explanations for Trump’s appeal.

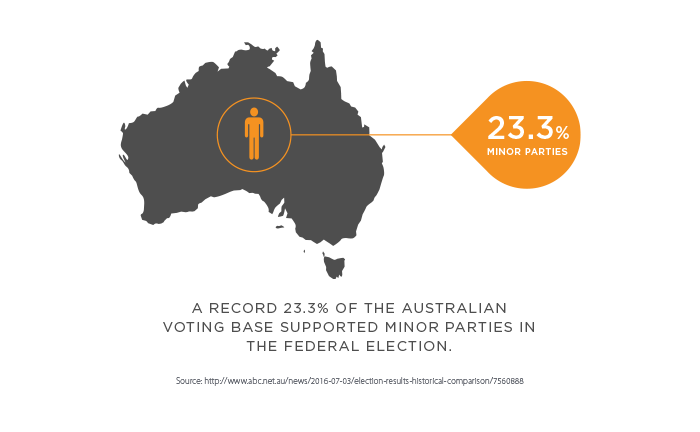

Australia’s own federal election does not provide an exact analogue, as its own element of unpredictability was less the dominance of a single unexpected force as the rise of several unexpected forces. Ben Oppenheim, a senior fellow at New York University’s Center on International Cooperation, comments: ‘Many polls in wealthy Western democracies have a consistent set of sampling biases: minority populations tend be under-represented; better-educated and more politically engaged people tend to be over-represented. Techniques like weighting can help adjust for that bias, but we're still going to get political surprises when groups that haven't been in the conversation, that haven't been systematically polled, become mobilised. Those are moments when the view we have of political life just no longer matches reality.’ In Australia, this led to an unpredictable first: Nearly one-quarter of the electorate did not vote for either Labor or the Coalition. A myriad of minor parties, as such, attracted a record share of the vote.

Social media—capturing more of the voice

Social media aren’t just bringing new groups into the conversation, they’re redefining the boundaries of community and paths to power

At a time when The Economist cites the evolution of media as a factor in the success of Trump and Brexit, it’s worth parsing the role social media play in opening pathways to previously unthinkable outcomes. ‘The battle for elections, issue campaigns, market share are all fought on social media now, and social platforms are designed to reward the most engaging content—not the most factually accurate,’ says Renee DiResta, a San Francisco-based technologist who studies the impact of social media on political movements. ‘The side that comes up with the most catchy hashtag, emotionally resonant narrative and viral meme is better positioned to grab attention.’

DiResta’s emphasis on the emotional resonance provided by radical views on social media hints at the human needs they fulfil—for a sense of stimulation and of connection. Considering that areas in support of both Trump and Brexit feature lower education levels and lower population density, might it be that the reason 50/50 politics seemed unthinkable to the ‘smart money’ is the very same thing that motivates these movements: the relative isolation and low social capital of these movements in the real world? Ironically, those with a limited profile in real life are often the most highly motivated to create a virtual community on social channels.

“Ironically, those with a limited profile in real life are often the most highly motivated to create a virtual community on social channels.”

While betting markets may have inaccurately pegged the likelihood of Brexit or the rise of Donald Trump, these events were not unpredictable. Predictions based on social media were more accurate. Twitter data gathered by TickerTags, a social media analytics tool, found that a ‘Leave’ vote was the most likely outcome of Britain’s EU Referendum before polls closed. It was not until late into the evening, after analysts had calculated the results of exit polls, that news organisations and prediction markets could verify which side had won.

So where do 50/50 politics leave investors and businesses?

For investors, conventional measures are likely to continue to understate the tightness of impending votes. The public’s proclivity to act independently of ‘expert opinion’ is likely to persist, given the only increasing popularity of social media as platforms for information and debate Treating all political events as potentially 50/50 outcomes, therefore—and accepting that these events are more uncertain—seems prudent.

For the business sector, the emergence of 50/50 politics presents a more challenging paradox. Businesses need to acknowledge that the policy debate is no longer being conducted exclusively among the traditional commentary class and that new patterns in social mobilisation are an unstoppable game changer. Business participation in the public debate has, therefore, never been more important, but ‘just’ participating won’t be effective. It needs to be in the right form and at the right level.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

insight

ASEAN Banking: Shaping the Future

The complete banking approach for this growing market.

research

China's Consumer: Sleeping Giant

There’s a tectonic shift underway in the Chinese economy.

research

Servicing Australia's Future

What will Australians and Australia look like in 2030?

For a full set of relevant disclosures, please visit the link below.

These publications are published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia on its Institutional website.

If you choose to access these materials, you agree that the Website Terms of Use apply. These publications are intended as thought-leadership material. They are not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in these publications is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in these publications constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in these publications is based on information available at the time of publication. While the publications have been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of these publications or the use of information contained in these publications. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with these publications.

If you are resident or located in the United States of America, you agree that you are not acting on behalf of a natural or individual (including yourself) “U.S. person” (as defined in Regulation S of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended) and you agree not to transmit or otherwise send any information on this website to any natural or individual person in the USA or to publications with a general circulation in the USA.

If you are resident or located in New Zealand, you are a “wholesale client” under the Financial Advisers Act 2008 (NZ), as amended.

Please confirm that the above statements are correct.