RESEARCH

2017: Globalisation in the rear-view

Download the PDF

By Richard Yetsenga, Chief Economist, ANZ | January, 2017

________

It’s not all bad. Calls to restore a 20th century industrial economy will create openings for intra-Asian regional consolidation and digital dominance for China.

Mr Trump’s ‘mandate’: Restore the early 20th century industrial economy using the pulpit of 21st century media

To understand the logic of President-elect Trump’s sharp breaks with Republican orthodoxy—threats of tariffs on US companies’ moving jobs abroad, treating the decades-long One China policy as a bargaining chip—you need to remember how technology enabled a very specific passion for the past to become kingmaker in US politics.

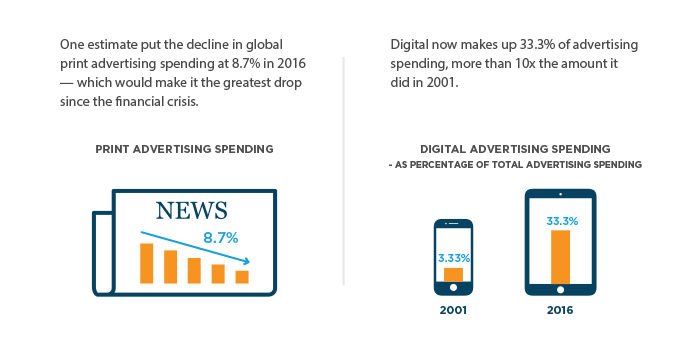

If Mr Trump’s unexpected victories in America’s former industrial heartland states demonstrate anything, it was the political efficacy of his promise to restore America’s industrial heyday supposedly snatched away by “takers”—China, Mexico, and Japan. Ironically, this call for the restoration of an earlier 20th century economy is being amplified by an exceptionally 21st century phenomenon: the decline of traditional media in favour of an ecosystem in which digital has a far greater weight and user-generated stories can rapidly grow and proliferate.

Source: Plummeting Newspaper Ad Revenue Sparks New Wave of Changes

It is a media landscape in which the Tweeter-in-Chief can present his narrative via a direct line to his followers, who can further deepen their sense of connection and empowerment by sharing such stories directly from their own social profiles, becoming news curators and arbiters of power in their own right. If you doubt how powerful that feeling can be, consider that public polling already shows a rise in optimism about the future among working class whites, Mr Trump’s demographic support base—an effect so powerful that some experts speculate whether it can boost their health even if questions remain about the effectiveness of his policies in economic terms. Broader, formal measures of consumer sentiment also show confidence around the highest levels since 2004.

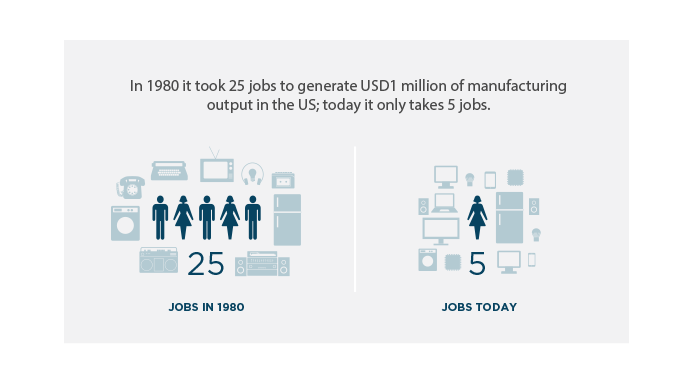

The irony of this situation, however, is that technology has been a core driver of the prosperity the US already possesses. Indeed, delivering on the promise to restore the 20th century industrial economy will be a near-impossible act, because there is a disconnect between the passionate politics of declining US manufacturing jobs that Mr Trump has deftly exploited and the actual root cause behind the loss. Analysis by economists such as Harvard’s Dani Rodrik has demonstrated that while trade has played a part in the decline of such jobs, in the developed world these losses have been primarily driven by technology. Trade policy will struggle to bring these jobs back.

Don’t assume this US backlash will be enough to put sand in the wheels of global trade

One shift that’s already sent a large signal is Mr Trump’s promise to reject the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Within Asia, this is likely to lead to increased airplay for China’s own version of regional integration via the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Indeed, as the president-elect takes the oath of office this month, Xi Jinping will be on his way to speak at Davos—the first attendance by a Chinese leader at this event. The signalling from China seems clear—it is open for engagement as the US is closing down.

Moreover, the world beyond the US generally hasn’t shifted from its broad support for global integration and trade. Even in the UK, Brexiteers have argued not against international integration broadly, but for different trade deals with different partners. Certainly some of the Trumpian rhetoric of supporting national economic actors under appeals to ‘fairness’ is now being echoed as far afield as India, where in December two of the country’s most successful entrepreneurs called for greater government support of home-grown companies against multinational competitors. Yet even in that example, the local companies in question benefit heavily from foreign investment, as commentators have pointed out. We strongly doubt the longevity of a style of politics that demands local entrepreneurs continue to benefit from the parts of global integration they like, but not suffer from the parts they don’t.

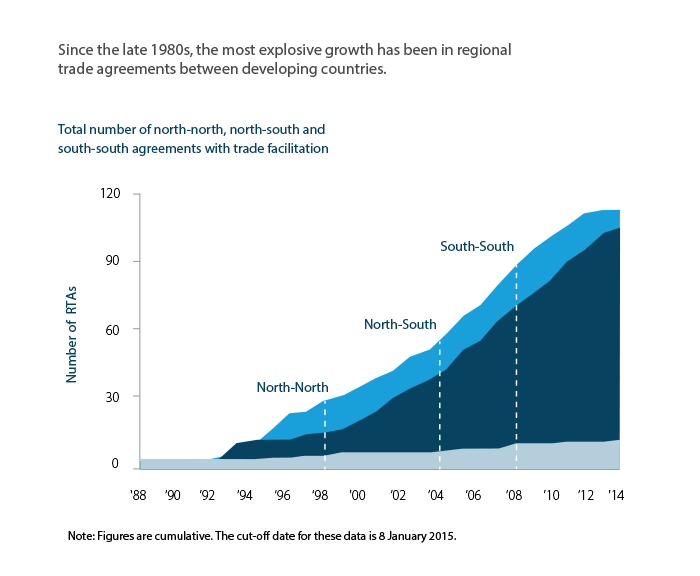

There are, of course, scenarios where the US could spark tit-for-tat trade wars of the sort that hark back to the 1930s. A more likely scenario, in our view, is that the US will isolate itself by pulling against the tides of economic preference elsewhere in the world. For APAC, the historical dynamic strongly favours continued regional integration. In fact, for APAC it is pretty straightforward. The region’s growth and development have only been possible because of an openness to trade and, selectively, to foreign capital. The US, conversely, has historically been much more closed.

Indeed, a major distinction between TPP and RCEP is that while TPP includes lofty goals such as sustaining the environment, implementing labour standards and combating corruption, the more modest RCEP is much more focused on the core issue of further facilitating the intra-Asian movement of goods between APAC countries. It is not a one-to-one substitute for TPP, but rather goes after the ‘low-hanging fruit’ of further value integration long under way:

Source: World Trade Report 2015

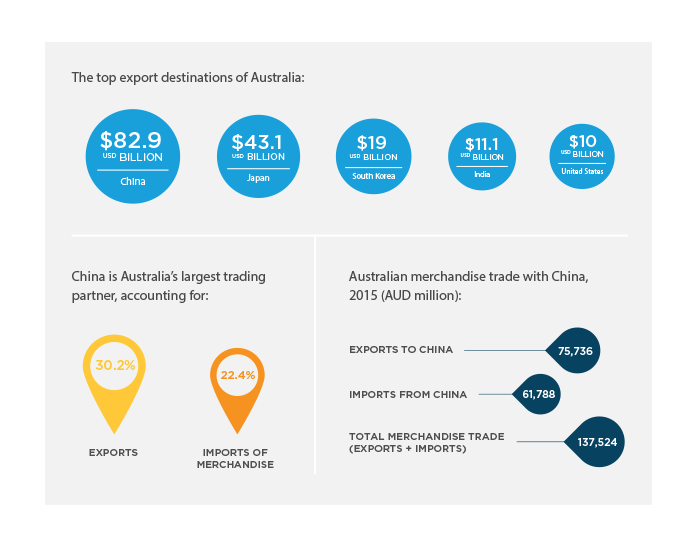

For the broader Asian region, we also need to be cautious about separating too discretely Mr Trump’s domestic policy agenda from his external one. Applying a fiscal stimulus of as much as a trillion US dollars to an economy already close to full employment must result in some combination of: (a) higher inflation as prices adjust to weed out excess demand; and/or (b) higher imports as excess demand is satisfied through the external sector. While raw material exporters such as Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand might be expected to be key beneficiaries of these developments, the effects, in fact, should be much broader.

Between 2013 and 2015 Asia was hit by tighter USD liquidity and weaker exports. As the Fed moves to hike interest rates further, the prospect of a double whammy with weaker exports seems far less likely. In fact, the latest data from across the region suggest only China has yet to see export growth return to positive territory on a sustained basis.

Source: OEC Australia profile and DFAT China trade resources

The opportunity cost of back-to-the-future

A further complication for the Trumpian agenda is that trade, and commerce generally, has quickly become quite digital. For instance, during my last visit to China, politics aside, what struck me the most were the advances in China’s digital economy. They seem more pervasive than almost anywhere else I’ve visited recently. As I wrote earlier, the tight and seamless integration of social, mobile and digital payments was extraordinary; I was one of the few people during my trip using cash at all. Admittedly, this applied only to my observations in Beijing and Shanghai; although they are among China’s fastest growing cities with the highest standards of living.

As well, in the context of the last decade, while we talk about transformations in manufacturing, there’s another number we shouldn’t miss—the value created by cross-border digital services:

The regulation and promotion of cross-border digital services was intended to be a key component of TPP. Parties of the trade agreement would consent to allow for the transfer of data cross-border, ban forced localisation of computing facilities, prohibit the forced disclosure of source code, and promote access to and use of the internet for e-commerce. While implementation of the TPP would have improved some regulations and the promotion of digital services, it’s unclear if TPP’s dissolution will have an adverse effect on cross-border trade in digital services.

While it is possible that, with the demise of TPP, countries could enforce mandatory localisation policies, the probability of an abrupt change doesn’t seem too high. As members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), many countries party to the TPP already abide by digital services standards under the APEC Cross Border Privacy Rules system. While APEC is non-binding, it does set a regulatory tone that will be difficult to strike against. Even China may become less forceful on issues around source code if it advances its regional agenda. Furthermore, driven by exponential price decreases in core technologies over the past decade it’s increasingly cheaper to build technology companies. Despite a potential unwinding of TPP, growth of e-commerce and digital services is likely to continue across APAC.

Let’s be clear

A Trump presidency represents a challenge to globalisation, not its end. Mr Trump’s rise is as much about citizen-initiated debate, as anything else. Almost certainly the world will be more fractious and less harmonious, with debate amongst governments adopting a tone we haven’t heard much of since the end of the Cold War. Coupled with a more protectionist stance from the US, this is likely to propagate businesses’ post-crisis hesitancy to make long-duration decisions—hiring staff is likely to continue to be prioritised over capital investment.

But not everything will be in President Trump’s control. Asia’s prosperity is clearly tied to a more open trading environment, and Asian leaders in recent months have been vocal in their support of a transparent and open trading system. In any case, digital trade has also been a source of explosive growth, and Mr Trump, as president, is likely to leave well enough alone. As well, a large fiscal stimulus will raise US demand for imports; regardless of President Trump’s trade policy gymnastics. It will be difficult, therefore, for him to upset a system of global trade anchored in Asia that has flourished in decades past, even if the US pulls away.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

research

The Paradox of 50/50 Politics

Conventional thinking says a backlash against globalisation is behind the biggest political upsets of 2016—but what if the issue is that the world no longer conforms to our predictive models? By giving voice to those previously without one, social media may have changed things more fundamentally.

insight

ASEAN Banking: Shaping the Future

The complete banking approach for this growing market.

research

China's Consumer: Sleeping Giant

There’s a tectonic shift underway in the Chinese economy.

For a full set of relevant disclosures, please visit the link below.

These publications are published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia on its Institutional website.

If you choose to access these materials, you agree that the Website Terms of Use apply. These publications are intended as thought-leadership material. They are not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in these publications is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in these publications constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in these publications is based on information available at the time of publication. While the publications have been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of these publications or the use of information contained in these publications. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with these publications.

If you are resident or located in the United States of America, you agree that you are not acting on behalf of a natural or individual (including yourself) “U.S. person” (as defined in Regulation S of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended) and you agree not to transmit or otherwise send any information on this website to any natural or individual person in the USA or to publications with a general circulation in the USA.

If you are resident or located in New Zealand, you are a “wholesale client” under the Financial Advisers Act 2008 (NZ), as amended.

Please confirm that the above statements are correct.