INSIGHT

Crossing borders: Transacting in Asia’s New Reality

Download the PDF

By Mark Evans, Managing Director, Transaction Banking, ANZ | June, 2017

Thought Leadership Event Summary — Third article of the 'Crossing Borders' series

________

The geopolitical shocks of last year—namely Brexit and the election of Donald Trump—dominated global headlines, with businesses understandably concerned about how the new reality of resurgent economic nationalism might affect cross-border trade and capital flows. As we’ve argued before, it shouldn’t be a cause for overreaction.

Rather, companies in Australia and New Zealand should focus on obtaining a more nuanced understanding of Asia-Pacific’s own new reality, characterised by evolving demand patterns and the changing role of China.

Providing such understanding was the aim of a series of events we held recently in key cities across ANZ’s home markets. These delivered multiple insights around two key themes. First, long-term shifts in demand are more significant than short-term volatility, despite the practical challenges the latter may present. Second, businesses seeking to make the most of opportunities in this new reality had better refine their thinking about China’s policy goals and changing economic profile—no easy task.

Shifting demand patterns

Much attention has been paid to the potential impact on this part of the world of Donald Trump’s trade policies but, as we’ve argued before, Asia is well placed to withstand the resurgent politics of anti-globalisation. Others agree: the Asian Development Bank recently forecast that Asia-Pacific economies (excluding Japan) would account for 60% of worldwide economic growth this year between them, even with a moderate slowdown expected in China. The prosperity of our businesses relies on the extent they can tap into this economic dynamism.

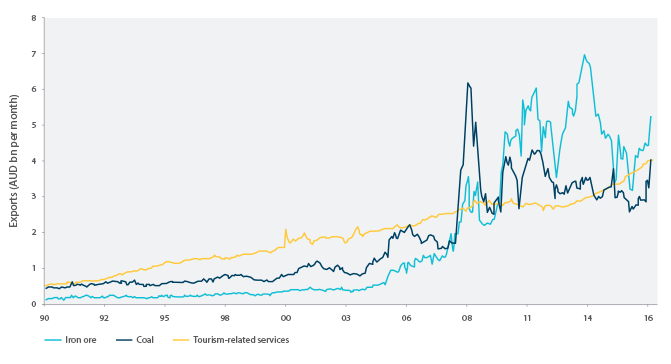

Australia is already seeing the impact of shifting demand patterns from Asian economies in this new reality. While resources exports have been subject to some volatility in recent years--and there is little doubt the China-led supercycle is over—other sources of demand from increasingly wealthy Asian populations is catching up, supported in recent months by a softer AUD.

Growth in services exports, in particular tourism, education and financial services, is rapidly compensating for weaker shipments of resources. Recent data shows the value of tourism-related services alone has almost caught up with iron ore. The constraints here are almost exclusively on the supply side, in the form of the number of flights it is possible to run from key markets, China in particular. The positive knock-on effects from expanding supply by adding more flights, such as more hotels, tourism jobs and service infrastructure, are considerable and nowhere near reaching their potential.

And, of course, foreign brands still enjoy some crucial advantages within China, especially when it comes to tapping the growing Chinese middle class’s demand for quality, trustworthy products. Consumer trust in suppliers is in fairly short supply in China, the keynote speaker at our events explained, particularly in the food supply chain. Hence the popularity of daigou sales, where orders are placed online in China for sales agents to pick up produce in physical stores overseas—including in Australia and New Zealand

—with receipts often required as proof of purchase in the specified location. Reinforcing the message of trust with discerning Chinese consumers will therefore be increasingly important.

FIGURE 1

Tourism exports now nearly as large as iron ore

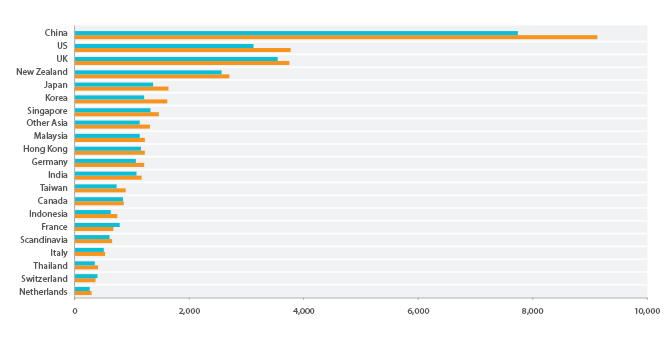

FIGURE 2

Tourism spending by country

Expenditure ($m)

Source: Tourism Research Australia, ANZ Research

Understanding a changing China

This means, of course, that businesses hoping to tap into these shifting sources of demand need a more nuanced understanding of China’s long-term development and the rationale behind its policies and decision-making. To say the least, this is not necessarily easy for those outside the country or those doing business across its borders, but it is increasingly important to consider in both long-term strategic planning and short-term tactics.

As our keynote speaker explained, taking account of China’s “multiple personalities” (see box) is a useful way of understanding the tension between broad policy aims and the sometimes opaque evolution of rules and regulations for companies transacting with the country.

Take a look at the country’s Five Year Plans (FYP). They contain detailed blueprints of economic development with measurable targets that cascade from the national to the provincial to the local level—for instance in the 13th FYP to roll out 30,000km of new high speed rail covering 80% of major cities by 2020. They also reveal the commitment to develop strategic new industries, with the goal of making them account for 15% of GDP. So while on one level they confirm that China’s demand for resources is far from over, on another they highlight those strategic sectors that are likely to take over from the old, investment-based economy, and which might well become as important to Australian and New Zealand businesses in future.

CHINA’S MULTIPLE PERSONALITIES

One useful paradigm for interpreting China explored at our events by Jason Yat-Sen Li, CEO of Yatsen Associates and long-time China expert, is to think of it as a country with multiple, sometimes contradictory personalities, rather than as a monolithic entity.

For instance, though the rule of the Chinese Communist Party is linked strictly to the country’s geographic boundaries, China’s personality as a self-sufficient civilisation stretches across national borders into diaspora populations. Another of China’s personality conflicts, Mr Li explained, arises from whether it is a communist or capitalist country: arguably it is the most successful ever of the former and is now one of the most important of the latter, all the while balancing the tensions inherent between political control and market freedom.

This tension is seen in its position as a hotbed of Internet innovation while it simultaneously has among the most restrictive Internet controls of any country. In commercial terms there is extraordinary freedom, as the success of the “BAT” trio (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent) has demonstrated.

The country is at least three years ahead of Australia in terms of mobile payments, Mr Li estimated, with full integration of onlineto- offline mobile payments for at least the past two. Meanwhile the most popular messaging app, WeChat (with over 880m monthly users and counting) has full banking integration to facilitate payments and transfers.

China can hardly therefore be described as a copycat economy. In fact it is incumbent on Australian and New Zealand businesses to try to harness some of its innovative spirit. To take just one example, the breadth of the online payments ecosystem in China has given rise to many more novel ways to monetise online audiences than just advertising. These include, for instance, the proliferation of live streaming services like Kuaishou, YY and around 100 others, for which collectively revenues are now around USD3bn (compared to annual box office receipts in China in 2016 of around USD7bn).

Finally, China embodies the contradictions between a laissezfaire economy and a centrally planned one. The kind of anything-goes innovation that characterises Alibaba’s meteoric rise (and crossing of sectoral boundaries) belies the staid progress of reforming China’s state-owned enterprises, not to mention the existence of rolling five-year economic plans.

One core theme running through the events wasthat of the tension between the need to react tactically to short-term volatility and to devise strategy to capitalise on long-term shifts. In that respect the tensions in Chinese policymaking appear explicable, while the opportunities from changing demand fundamentals, and structural economic shifts, remain clear.

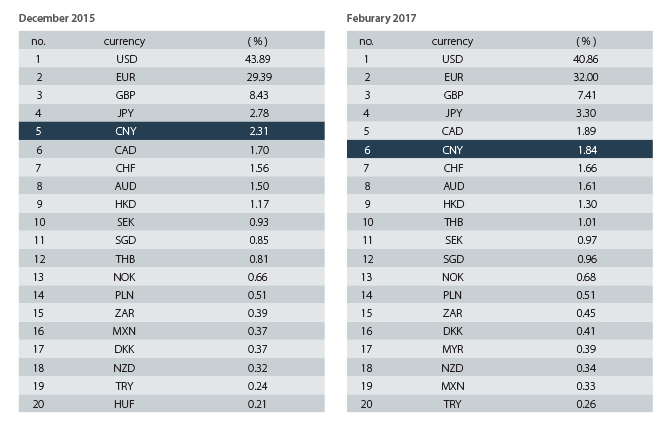

At the same time the FYPs also reveals the tensions between long-term strategy and short-term policy. Take the government’s hope for more and more international business to be conducted in renminbi—reiterated in its commitment in the 13th FYP to continue with the internationalisation of the currency. This necessitates exposing China’s financial system more fully to global market forces, something that is sometimes hard to square with the government’s overriding commitment to promoting stability.

Shifts between the two priorities can put foreign companies doing business in China in an awkward position. After taking several steps to liberalise the flow of capital across its borders in recent years, and to allow the market to play a greater role in the fixing of the value of the renminbi, volatility in the value of the currency (down 6.6% against the USD through 2016) and the level of its foreign exchange reserves (which fell by nearly USD320bn in the same period) made Beijing think more carefully about this process. Last November, the authorities took steps to impose some exchange controls (via its “window guidance”), some of which hit foreign companies’ abilities to remit dividend payments. It looks like these controls have recently been relaxed—but pinning down what is and isn’t allowed is far from straightforward.

FIGURE 3

RMB’s share as an international payments currency

Customer initiated and institutional payments.

Messages exchanged on SWIFT. Based on value.

Source: SWIFT RMB Tracker,

Perhaps unsurprisingly, such measures mean international usage of the RMB has diminished in recent months. But such short-term fluctuations don’t change the long-term calculus, or negate the goals set out in the 13th FYP. On the capital account, the plan makes clear that the bid to make the RMB an international investment currency will continue. On the current account, pressure to transact more in renminbi across borders will grow, as Chinese exporters and importers seek to reduce the risks of dealing with a third currency—typically USD—in their international contracts.

Long-term strategy, short-term tactics

As for Beijing, so for the C-suite. Too much attention has been paid to political events in recent months, removing the focus from fundamental shifts in Asia-Pacific economic relationships that continue to progress, and which businesses at home are well placed to capitalise on. All companies that seek to do cross-border business in the Asia-Pacific’s new reality will need to adjust both their short-term tactics and their long-term strategy accordingly.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

insight

Crossing Borders: Navigating the New Reality of International Business

Globalisation has redefined how businesses operate, enabling them to reach more customers, improve efficiency and ultimately become more profitable. However, in an increasingly complex world, the benefits that have been delivered by globalisation can no longer be taken for granted.

insight

Who Wants Disruption Anyway?

If any aspect of banking seems ripe for technological disruption, it’s cross-border transactions. Sending money from one country to another is often a slow, cumbersome and opaque process.

insight

Cross-border Transactions in a 'Post-global' World - No Need to Panic

For the many businesses in australia and new zealand whose operations depend on the unimpeded flow of transactions and capital across international borders, it’s a difficult time to be optimistic.