INSIGHT

No TPP, no problem? Examining Asia’s trade resilience

Download PDF: English | Chinese

Richard Yetsenga, Chief Economist, ANZ | Khoon Goh, Head of Asia Research, ANZ | February, 2017

________

The politics of anti-globalisation are in the ascendant. US President Donald Trump’s pledges to rip up trade deals and impose border taxes on imports appealed to many voters, as did on the other side of the Atlantic the prospect of the UK’s exit from the EU.

On the surface, Asian nations have good reason to worry. Not only have they, and China in particular, been the focus of President Trump’s ire, but they have also been prime beneficiaries of freer trade and capital flows in recent decades.

Sixty years ago Asia was the world’s poorest region, but it now accounts for a third of the world’s GDP and is likely to reach more than 50% by 2050. In 1990 more than 60% of East Asia lived in extreme poverty; by 2013 only 3.5% did. In China alone 680m people escaped extreme poverty between 1981 and 2010.

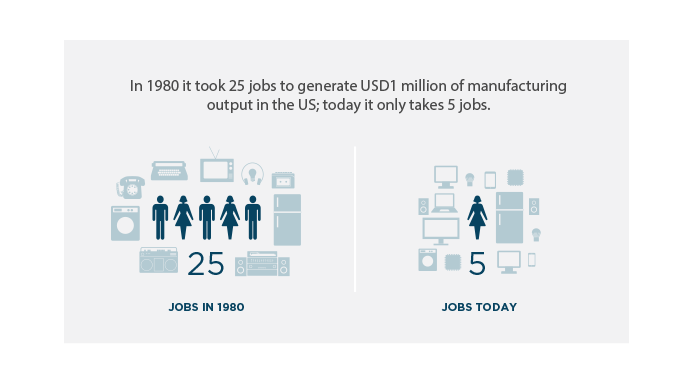

As we’ve argued elsewhere, the forces that have driven such incredible gains (and, incidentally, eliminated jobs in developed economies like the US) are linked to technological progress as much as free trade per se, and won’t be rolled back even if President Trump follows through with his pledges. A tit-for-tat trade war is possible, if unlikely, but even if it does transpire, the US may end up isolating itself while much of the rest of the world – and Asia Pacific, in particular – continues to seek closer integration.

There are actually several good reasons to be optimistic about Asia’s resilience

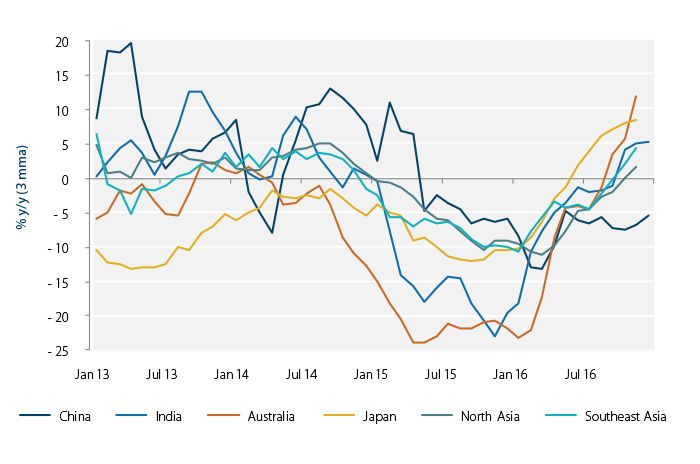

In the short term, for one thing, it is much better placed than it was even a few years ago to withstand US-led disruption. In 2013 Asia suffered from the double whammy of tighter US liquidity and weaker export data, but the latest figures (see Fig.1) show export growth is returning to most Asia-Pacific nations (China, undergoing more dramatic structural reform, being the exception).

Ironically this trade growth could very well be sustained by US demand. If President Trump makes good on promises for a trillion-dollar fiscal stimulus, import demand cannot but rise (along with inflation). This will benefit raw material exporters in the Asia-Pacific like Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, and also the region more broadly, thanks to the complex supply chains that have evolved in recent years.

On the downside this means US border taxes could have unintended ripple effects, rather than hitting just China. However, the impact of such measures in Asia is unlikely to be as severe as it is in Mexico, which has seen a greater direct relocation of US production capacity. Also, ASEAN countries like Vietnam, which has evolved as a compelling investment destination in its own right as well as a “+1” solution to rising costs in China, are well placed to benefit even if the Sino-US trade relationship sours.

Considering the longer-term, regional integration looks set to continue even if the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) is truly finished. For one thing, there will be a lot more focus on China’s role as the champion of multilateral trade deals, through initiatives like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes China and the 10 members of ASEAN as well as the region’s other major economies: Japan, India, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea.

Admittedly RCEP is not as ambitious as the TPP in terms of “next generation” issues like cross-border digital services. But the fact that these are increasingly crucial to the region’s economies (as we’ve noted before), and that bodies like APEC have already established digital services principles that will be hard to roll back, means conditions are good for the continued growth in Asia of this kind of commerce.

Finally, it’s not just trade flows that dictate prosperity: cross-border investment of the type that Asia has typically welcomed plays a vast role. Putting aside for a moment the very real geopolitical issues that can complicate such matters, China’s transformation into an exporter of capital and owner of more productive assets outside its borders should help cement economic integration within the region.

This is a natural economic progression, as seen with Japan since the bubble years and South Korea more recently, and goes beyond Beijing’s short-term concerns about the impact of capital outflows on its currency. On the back of initiatives such as RCEP and One Belt, One Road, Chinese companies will be seeking opportunities abroad as the domestic economy matures. Ultimately cross-border investment will create more wealth for recipients than simple merchandise trade.

Of course, it doesn’t pay to be too Panglossian, and in a febrile political environment politics often trump economics (pun intended). But Asia remains in a good position to continue to reap the rewards of freer trade and investment flows.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

insight

China in 2017: Resilience at home, adversity abroad?

China’s changing economy is robust enough to cope with domestic challenges but a volatile international environment will pose the toughest questions for Beijing’s policymakers.

research

2017: Globalisation in the rear-view

Calls to restore a 20th-century industrial economy will create openings for intra-Asian regional consolidation and digital dominance for China.

research

The Paradox of 50/50 Politics

Conventional thinking says a backlash against globalisation is behind the biggest political upsets of 2016—but what if the issue is that the world no longer conforms to our predictive models? By giving voice to those previously without one, social media may have changed things more fundamentally.