INSIGHT

China in 2017: Resilience at home, adversity abroad?

Download PDF: English | Chinese

Raymond Yeung, Chief Economist, Greater China, ANZ | January, 2017

________

China’s changing economy is robust enough to cope with domestic challenges but a volatile international environment will pose the toughest questions for Beijing’s policymakers

China’s 2016 GDP figures provided a measure of reassurance that its economy remains among the world’s most resilient as well as fastest-growing. It managed real GDP growth of 6.7% last year despite facing a host of challenges, including the fallout from an unexpected currency devaluation and sharp corrections in domestic stock markets -- shocks that could have caused recessions, and even led to major bailouts, in some advanced economies.

This resilience is worth keeping in mind when considering the tests China faces in the Year of the Rooster. These include structural reform, competing monetary policy objectives, and a new, much rockier era of relations with the United States, whose new president, Donald Trump, has threatened to impose punitive tariffs on its imports.

While we are optimistic that China can manage its domestic economic agenda with a degree of flexibility, international issues will pose tougher questions, even if a full-blown trade war with the US seems unlikely.

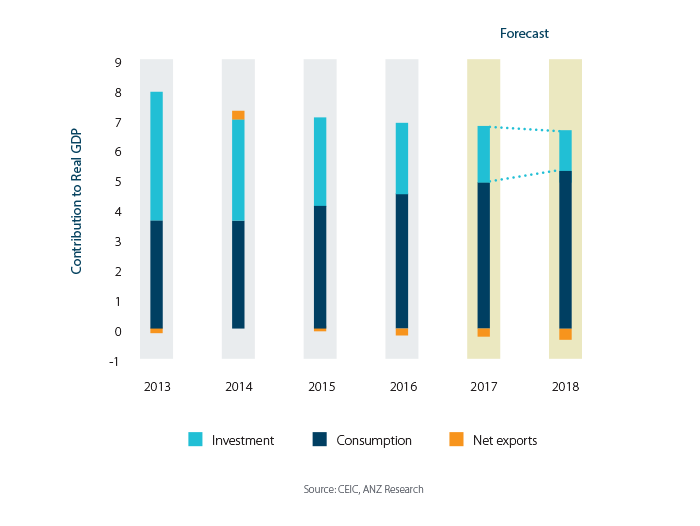

FIGURE 1

China's GDP Growth by Expenditure

Domestically resilient…

Full-year growth figures aside, there were plenty of other positive signs for China’s domestic economy towards the end of 2016. These included a mild recovery in the industrial sector, with the headline purchasing managers’ index rebounding to a two-year high, and the return to positive producer price inflation in September after more than four and half years of contraction -- a landmark event that spoke to the efficacy of supply-side reform and capacity reduction in helping avoid a deflationary trap.

True, the outlook for manufacturing and construction remains sluggish, but China’s relative health is being reinforced by progress in rebalancing the economy. Anyone who visits the country cannot fail to see this secular shift: a large part of China’s economic vibrancy is now coming from services and domestic consumption instead of low-level manufacturing and investment, as the incredible rise of mobile-based services (and supporting logistics) attests.

Meanwhile, the geographic profile of growth is also changing, with inland regions picking up even as coastal provinces slow. In one striking contrast, the GDP of Liaoning, the largest of three north-east industrial provinces, shrank last year (-2.2% Q3 ytd) while that of Chongqing, fast becoming a major production hub in south-west China, grew in double digits (+10.7%)1.

All this points to resilience as the focus on “supply-side structural reform” intensifies in the run-up to the 19th Communist Party Congress in the autumn, after which Xi Jinping will have unprecedented political capital to pursue this ideology as the cornerstone of the 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020). It also suggests a certain flexibility may be possible in formerly sacrosanct economic policy commitments, such as the annual GDP growth target, due to be announced at the National People’s Congress in March. The State Council may widen the target range to 6%-7% from 2017 onwards, allowing a degree of breathing room while also delivering the growth needed to fulfil another core promise: to double GDP per capita between 2010 and 2020.

…and internationally resolute

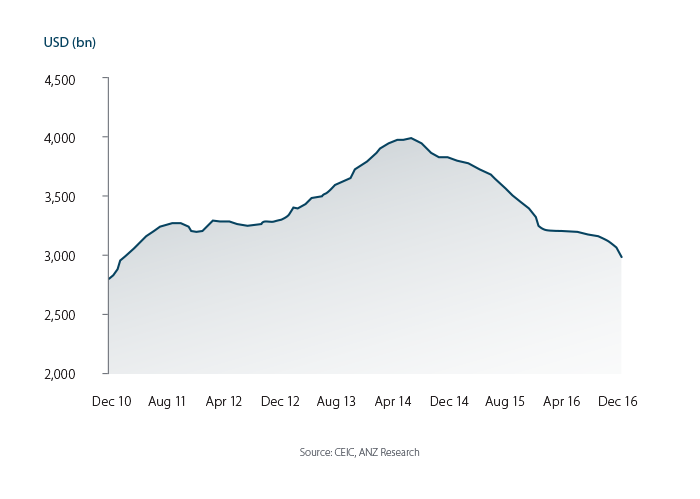

More nimble policy will also be required to deal with China’s external challenges in 2017. For one thing, these complicate the delicate task facing China’s authorities of managing currency volatility and stemming capital outflows without jeopardising international confidence in the country’s capital markets, or the hard-won status of the renminbi as a global investment currency.

This is partly because China can’t have everything it wants. It can’t control its own money supply, exchange rates and interest rates and allow free capital flows across its borders. It may have taken some steps to re-impose limits on such flows (such as restricting certain types of outbound M&A) but the reality is Chinese corporates and financial institutions are already part of the global marketplace. The movements of funds associated with trade, M&A, portfolio investments, and cross-border financing are becoming unavoidable.

To prevent further depletion of foreign exchange reserves, it may be necessary to float the yuan. It may be that this degree of policy flexibility is too much to expect in 2017. And with US$3trn in reserves still at its disposal, few can doubt China still has the firepower or resolve to defend the renminbi against most, if not all speculation. Yet the reality of cross-border flows -- and the costs of defending against them -- are only likely to become more apparent in 2017.

FIGURE 2

China Foreign Reserves

Trump risk

China’s foremost international challenge is, of course, a Trump administration in the US. In a conference of some 40 economists in Shanghai in early January, every single one named “Trump risk” the biggest issue facing China this year. Much of this relates to geopolitical rivalries that won’t be easily resolved. But focusing purely on the economic relationship, there are a number of factors we’d point to that suggest a full-scale trade war is unlikely.

In a conference of some 40 economists in Shanghai in early January, every single one named “Trump risk” the biggest issue facing China this year.

One is that for the same reason China can’t ignore the fact that cross-border flows are a reality of modern business, US policy will have to recognise the need to protect American interests overseas. The value added on iPhones assembled in China, for example, is minimal, so a tax on the import from China of products back into the US would in effect be a tax on Apple’s profits. Thousands of other US companies are in the same boat.

Another consideration is that Mr Trump’s modus operandi suggests a preference for face-to-face bilateral dealing over multilateralism -- especially the kind of multilateralism typified by regional trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership. As a businessman, Mr Trump is more likely to seek to cut a mutually beneficial bilateral deal with China than impoverish American businesses and consumers through a destructive trade war. Of course, this will require Beijing to respond proportionately to his actions rather than his rhetoric.

In short, China’s policy agenda for 2017 is perhaps the most testing it has faced in decades. The signs are good that its economy has the resilience to meet domestic challenges, though only time will tell whether its policymakers have the flexibility to contend with the international ones.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

research

2017: Globalisation in the rear-view

Calls to restore a 20th-century industrial economy will create openings for intra-Asian regional consolidation and digital dominance for China.

research

The Paradox of 50/50 Politics

Conventional thinking says a backlash against globalisation is behind the biggest political upsets of 2016—but what if the issue is that the world no longer conforms to our predictive models? By giving voice to those previously without one, social media may have changed things more fundamentally.

research

China's Consumer: Sleeping Giant

There’s a tectonic shift underway in the Chinese economy.