RESEARCH: Asia’s new investment nexus

Building on the promise of the Greater Mekong Region

Download the PDF

By Eugenia Victorino, Economist, ANZ | December, 2016

________

The Greater Mekong Region (GMR), which spans Southwest China, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, is not only one of the most strategically important regions in Asia; it is fast becoming one of the continent’s most dynamic investment destinations.

New infrastructure developments in the frontier “CLMV” markets mean the dream of land routes connecting Asia’s largest economies, India and China, and the continent’s hinterland to its southern seaports, is becoming a reality. The proliferation of special economic zones (SEZs) and industrial parks has greatly improved the investment environment, as have political developments in recent years, notably in Myanmar. The youthful and comparatively cheap labour forces of these countries means they are well positioned to capture manufacturing work shifting from neighbouring countries that have already climbed the value (and cost) chain – as well as to benefit from the transfers of expertise and technology that greater cross-border commerce bring.

This is the theory, at any rate. In practice, investing in the GMR’s frontier economies is still not for the faint of heart. Though the environment has improved markedly in recent years, the diversity of standards in the region’s infrastructure, legal systems, bureaucratic procedures, and talent pools mean the “frontier” status of CMLV economies is still, in many respects, well deserved. Yet at the same time, with growth in exports from the region outstripping that in the rest of Asia, and its markets likely to become more attractive as the region forges into higher-value industries, it is an area no multinational can afford to ignore in formulating an Asia strategy.

This paper examines the status and future of the economies of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, and their attractiveness as investment destinations, drawing from a number of recent ANZ research initiatives. These include a landmark study of corporate usage of SEZs in the region, produced in collaboration with the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and a panel discussion on investing in GMR economies held in Singapore in November 2016 that included senior executives from multinationals with long histories in the region, as well as ANZ economists and regional business leaders.

These initiatives produced a number of key findings on the projected development of CLMV economies, the impact of SEZs and new transport corridors on the region, and challenges the private sector faces in making the most of the opportunities presenting themselves in Asia’s most exciting investment frontier.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: VIETNAM IN THE VANGUARD

It is a mark of the speed of development of the GMR that since the 2008-09 financial crisis, exports from the region have been growing at over twice the global rate: during this period GMR exports have seen compound annual growth of 10% year on year, while world trade has been growing at 4.9%.1

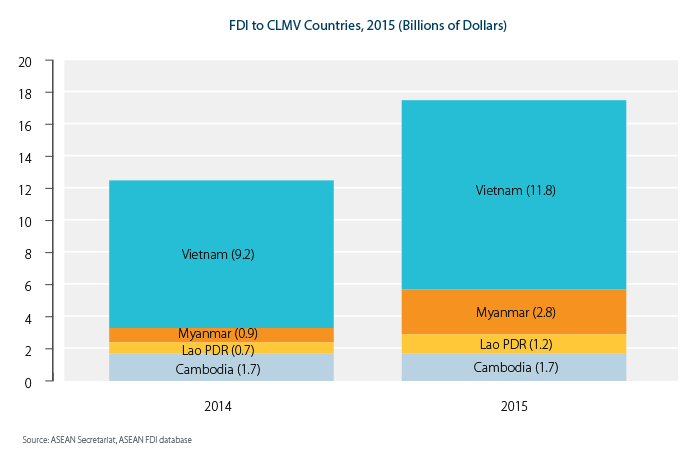

19.3% year on year. In fact, Vietnam has provided the model for other frontier GMR economies, serving as an “FDI magnet” and demonstrating the region’s potential to transform into a manufacturing powerhouse. In the five years to 2015 Vietnam attracted some USD65 billion in FDI, of which 70% went into manufacturing.2 In 2015 foreign companies ploughed USD11.8 billion into the country, two-thirds of the total allocated to the CLMV economies (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

FDI Magnets

Until relatively recently, the majority of Vietnam’s exports were low-value-added, labour and resource-intensive goods. But like Thailand before it, Vietnam has rapidly climbed the value chain, becoming a crucial part of the global supply chain for high-end consumer electronics. The largest investors in the country are now multinationals like Samsung and Taiwan’s Hon Hai Precision Industry: Samsung alone has invested almost USD7 billion there.3

Investment of this kind has had a multiplier effect, since multinationals of this scale can also encourage suppliers and subcontractors to set up in the country near their assembly plants. ASEAN reported in mid-2016 that at least 97 firms had set up such operations in Vietnam to supply parts and accessories to Samsung, for example.4

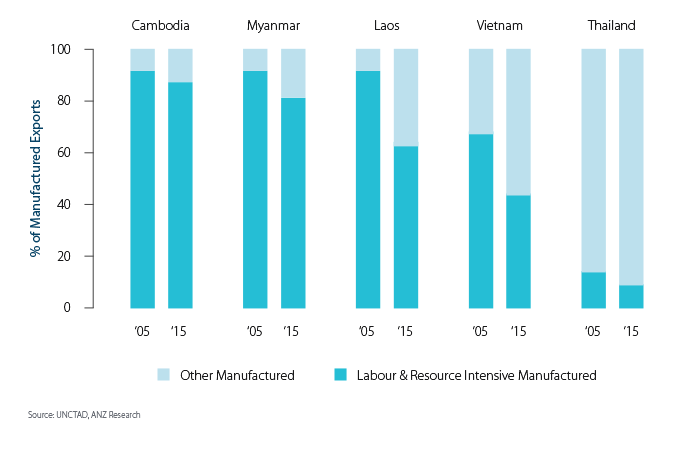

This “snowball” phenomenon means that the graduation from low-end to higher value-added manufacturing can be swift. Although Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar still trail Vietnam by some distance, and are far smaller economies, they have seen the start of a similar transformation in recent years. ANZ analysis shows that in the past decade, the share of labour and resource-intensive manufactured exports has fallen in every CLMV economy and in Vietnam’s case is now less than half of its total manufactured exports (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Climbing the Value Chain

A growing domestic opportunity

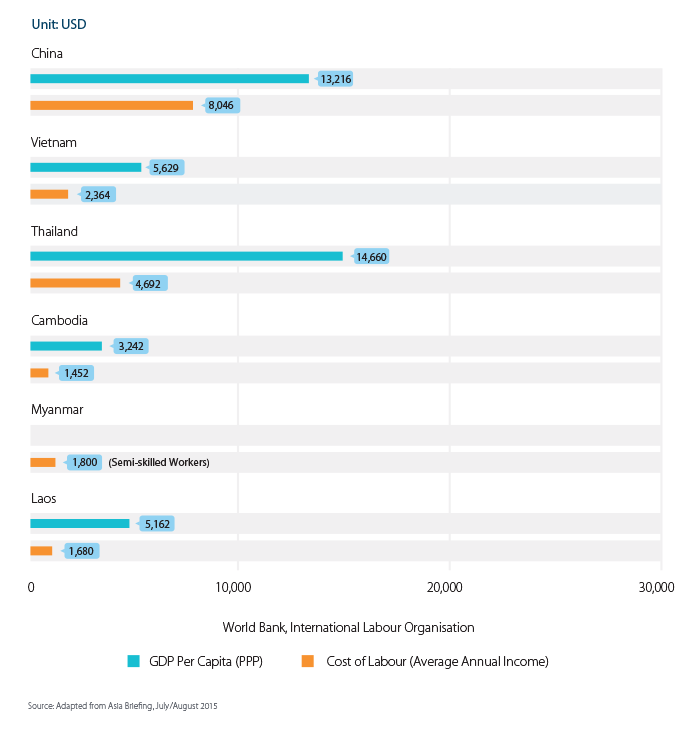

Why does this matter? First, multinationals considering the most cost-effective way to source more advanced production facilities in Asia are already finding the frontier economies of the Greater Mekong Region a crucial part of their “+1” strategies. As labour costs in China and Thailand have risen, so the efficiencies of shifting production to other Mekong nations are more apparent (Figure 3). The raw demographics are also appealing: one-quarter of Vietnam’s population, for instance, is between 10 and 24 years old, and the median age is 29.5

FIGURE 3

Labour Costs in Comparison

Secondly, the increasingly wealthy population base of these countries is an increasingly attractive source of demand in its own right. Boston Consulting Group estimated that the number of middle-class affluent Vietnamese (with income of USD714 per month or more) would double in size between 2013 and 2020, growing to two-thirds the size of Thailand’s middle class population.6

Myanmar, meanwhile, has a population of around 50 million people that until only recently was largely cut off from global commerce – making it one of the world’s last, and largest, untapped markets. In ANZ’s survey of usage of the region’s SEZs, Myanmar was the only frontier economy where production was seen as viable to service a domestic market (while in Vietnam, already, more than half of respondents said they were producing to meet local demand). B-to-C industries that haven’t considered how to meet burgeoning demand in Vietnam and Myanmar are already behind the curve.

BEHIND THE TRANSFORMATION: TRANSPORT CORRIDORS AND SEZS

The changes sweeping GMR economies are in part due to policymakers’ recognition that they stand on the brink of a unique opportunity to serve businesses in the greater ASEAN region, as well as Asia’s manufacturing powerhouse, China – provided they take steps to make the investment environment more appealing for global companies.

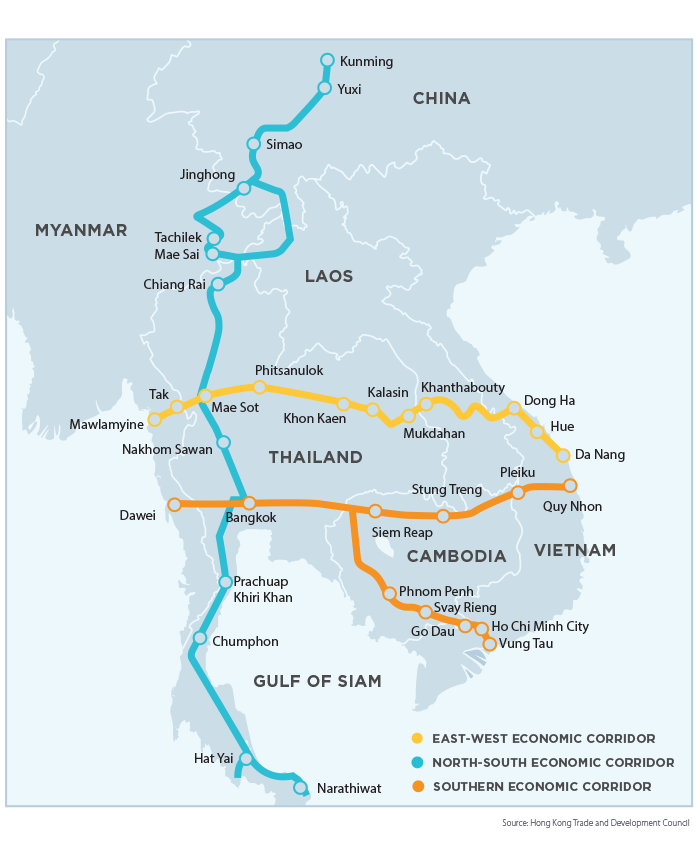

To that end, Mekong governments have prioritised the establishment of transport corridors in the form of road and rail routes linking ports and SEZs across the region. The main routes define economic corridors that run from north to south, linking Bangkok with China’s Yunnan and Guangxi provinces and passing through eastern Myanmar, northern Laos and northern Vietnam; and east-west, connecting Mawlamyine, a city on Myanmar’s east coast, to the Vietnamese port of Da Nang, through central Thailand and Laos, potentially linking the Indian Ocean to the rest of the ASEAN region. A third, southern, corridor links the ports of Dawei in Myanmar to Quy Nhon and Vung Tao in Vietnam, through central Thailand and Cambodia (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

Greater Mekong Transport Corridor

Already, SEZs along these corridors are reaping the benefits. ANZ’s survey of clients’ usage of these zones showed that the Savan-Seno SEZ in Laos’s Savannakhet province, on the border with Thailand, is well placed to help the region’s smallest economy go from “land-locked” to “land-linked”, to coin a favourite phrase of Lao government officials, as firms use it to implement their “Thailand+1” strategies and take advantage of Laos’s lower electricity and labour costs. Similarly the Dragon King SEZ in Cambodia, on the country’s Route 1 highway along the southern economic corridor, is already being used in a similar “Vietnam+1” strategy.

Choose your SEZ carefully

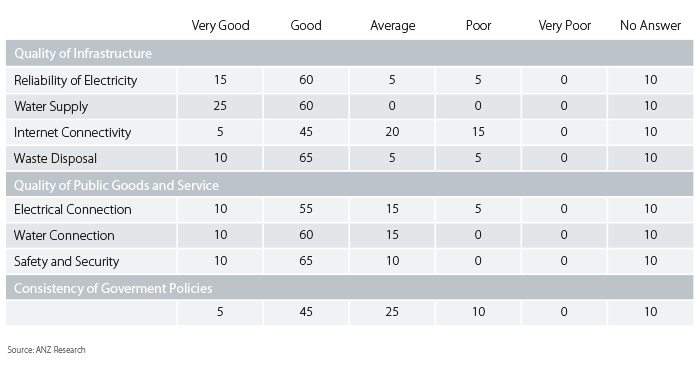

Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia are still a long way behind Vietnam both in the number of such zones and industrial parks and their operation. The number of industrial zones in Vietnam rose from around 200 in 2008 to 400 in mid-2015. Most, according to ANZ research, are ranked as good or very good in terms of providing infrastructure and services (see Figure 5). They are less consistently praised on factors such as Internet connectivity and the consistency of government policies – although 50% of respondents still ranked them good or very good on these factors.

FIGURE 5

Vietnam Industrial Parks’ Business Environment (% respondents to ANZ survey)

Those in Cambodia, by contrast, are generally seen as underperforming, with high logistics costs and average to poor SEZ management a common complaint of survey respondents, despite improved transport connectivity. A lack of industrial diversity is perhaps one culprit: Cambodia’s preferential access to EU markets has skewed investment towards the textiles sector, with higher value-added industries yet to invest substantially, in part due to labour issues (examined in the next section).

Laos, by contrast, has already seen some high-tech investment in the Savan-Seno SEZ, based on logistics advantages from the East-West Economic Corridor. Low and stable utilities costs, competitive labour rates, and tax holidays and exemptions were also cited as key attractive factors (although security management was identified as an issue).

Meanwhile in Myanmar, while the quality of SEZs varies, the Japanese-run Thilawa SEZ (which became operational in 2015) is already gathering plaudits for its efficient management, modern and green infrastructure, and one-stop shop investor approach. However, whether regulations within the zone will be streamlined sufficiently to take investment to the next level is still uncertain.

REGULATIONS, TALENT AND OTHER REMAINING CHALLENGES

If frontier economies hope to follow Vietnam in becoming FDI magnets and producing more sophisticated goods, addressing bureaucratic complexity and regulatory uncertainty is of paramount importance. While the ANZ survey showed that tax incentives, efficient customs clearance and consistent government policy were among the most important factors in luring investment to Vietnam initially, the ongoing success of its industrial zones is related both to the infrastructure that they provide (transport, reliable power supply and so on) as well as the streamlining of regulations, rather than these initial “carrots”.

Solving the software issue

Across the GMR, in the assessment of experts at the ANZ panel discussion, actual utilisation of “hardware”, in the form of new roads, railways, bridges and ports, remains lower than had been hoped when these investments were approved. This is because issues remain with the “software” necessary to run these facilities efficiently, and many are beset by administrative and legal burdens.7

In theory SEZs can help mitigate these problems; indeed it is part of their raison d’être. But in practice investors in the region are still challenged by entrenched bureaucracies and the sometimes uncertain application of rules.

Some uncertainty is understandable in places like Myanmar, which is grappling with the herculean task of creating new investment legislation en bloc. But while new labour and companies laws might resolve some issues, the approach to other regulations within SEZs requires further streamlining: in ANZ’s research one firm shared an example where architectural drawings of a plant to be built had to undergo revisions and re-submissions almost 60 times before obtaining final government approval.

More broadly, for the region’s economic corridors to achieve their potential, better intra-governmental co-operation is also required, especially when it comes to customs procedures and other cross-border regulation. Despite efforts to streamline processes, border arrangements often remain time-consuming and are subject to approval by local officials. And while progress has been made in reducing tariffs to ease cross-border commerce, both through regional trade initiatives under the auspices of ASEAN and bilateral deals, non-tariff barriers to trade (such as varying safety standards) remain a problem.

A labour tipping point?

Regulatory grey areas can often be navigated, provided investors obtain reliable partners and do thorough on-the-ground research before committing to a project. Talent shortages, though, may prove a less tractable issue.

For one thing, a skills gap means SEZ investors feel they put too much time into micro-managing staff. Some companies are attempting to address these gaps by investing heavily in training. In Myanmar’s Thilawa SEZ, for example, one firm surveyed by ANZ often sends local workers to Vietnam for month-long periods to study things like welding, customs procedures and human resources. In Laos, another has tie-ups with universities and vocational education institutions to provide formal training.

One potential issue with such an approach is that the investment becomes a sunk cost should newly skilled workers leave to pursue other opportunities. Moreover, even at this relatively early stage in their economic development, frontier GMR economies face a labour tipping point wherein spillover effects from the kind of “+1” training strategies mentioned above will raise the cost of skilled labour, lessening the advantage of setting up in these markets in the first place.

ANZ research found that the skills tipping point to higher salaries is surprisingly low and is dictated by just two factors: a basic knowledge of English and a basic knowledge of manufacturing and production line processes. “Upgrades” in one or both of these areas can lead to high labour turnover as well as rising costs for semi-skilled labour. This effect has already been noted in Cambodia, with some firms in SEZ increasingly offering higher wages to try to retain staff, and is becoming apparent in other GMR economies.

CONCLUSION: CARPE DIEM

Such is the region’s dynamism and potential that the issues outlined in this report are far from deal-breakers for companies considering investing in GMR economies. Cambodia, Laos and particularly Myanmar have taken dramatic steps in recent years to improve their investment environments, and are reaping the rewards, meaning further progress is likely in the years ahead. Indeed, by some measures Myanmar is already evolving beyond a “frontier” market to join Vietnam as one of the world’s most promising emerging economies.

With many “hardware”-related connectivity problems on their way to being resolved through the region’s transport corridors, the race is on for GMR nations to address some of their more persistent “software” issues and labour market constraints. This requires the ongoing collaboration of public and private sector actors: governments need to put in place consistent and transparent regulations and education policies that deliver trainable workforces, as well as collaborate to reduce the complications of cross-border commerce.

Investors, for their part, need to invest in training and forge links with vocational institutions to offer students workplace experience and embed skills at a younger age. There is also significant potential in “train the trainer” initiatives that are already emerging in places like Myanmar and Cambodia, where local SEZ workers are increasingly learning from their Vietnamese counterparts. The transfer of skills from Vietnam to other Mekong economies is a clear regional dynamic that suggests the region can address its own capacity issues. Given the experience many investors have in international markets, there is also a role for the private sector to play in sharing views and best practices in investment and infrastructure with regional governments, and in bringing its expertise to bear in the development of local industry clusters.

While much ground remains to be covered, there is little doubt a critical mass now exists for the resolution of both the GMR’s “hardware” and “software” related issues, and that the region is about to assume a more prominent position in the Asian investment landscape. As always, the investors who move early to seize on this opportunity – by finding the right partners, forging local relationships and making positive contributions to the development of the region’s economy and labour market – are those who will benefit most when the GMR hits full stride.

1. Source: ANZ Greater Mekong Outlook, 1 November 2016

2. Source: ANZ Greater Mekong Outlook, 1 November 2016

3. Source: FDI forecast warily brightens

4. As noted in the 2016 ASEAN Investment Report

5. Source: Keep an Eye Open on the Future of Vietnam FMCG Industry

6. Source: Vietnam’s Middle Class Set to Double by 2020: BCG

7. It must be noted that hardware-related connectivity issues are still an issue as well. If goods are exported from Vietnam from Cambodia by rail, for example, different axle gauges require offloading and reloading of cargo, greatly increasing the time taken. A recent review of Mekong region transport plans notes that most progress has been in the road sector, although the formation of the Greater Mekong Railway Association in 2013 promises to improve co-ordination in rail transport. ADB, GMS Secretariat, “Initial Review of the Greater Mekong Subregion Transport Sector Strategy , 2006-2015”.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

research

Wages - And Ambitions - Rise As Mekong Workforce Enters A New Era

Can Mekong countries foster skilled labor while retaining competitiveness?

research

Along The Mekong, A New Regional Network Takes Shape

Transport corridors set to enhance connectivity and accelerate commerce.

research

Making it in the Mekong: Lessons on investing in Asia’s new growth frontier

The evolution of the Greater Mekong and how businesses can truly capitalise on the opportunity.

For a full set of relevant disclosures, please visit the link below.

These publications are published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia on its Institutional website.

If you choose to access these materials, you agree that the Website Terms of Use apply. These publications are intended as thought-leadership material. They are not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in these publications is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in these publications constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in these publications is based on information available at the time of publication. While the publications have been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of these publications or the use of information contained in these publications. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with these publications.

If you are resident or located in the United States of America, you agree that you are not acting on behalf of a natural or individual (including yourself) “U.S. person” (as defined in Regulation S of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended) and you agree not to transmit or otherwise send any information on this website to any natural or individual person in the USA or to publications with a general circulation in the USA.

If you are resident or located in New Zealand, you are a “wholesale client” under the Financial Advisers Act 2008 (NZ), as amended.

Please confirm that the above statements are correct.