RESEARCH: Making it in the Mekong

Lessons on investing in Asia’s new growth frontier

Download the PDF

By Eugenia Victorino, Economist, ANZ | November 2016

________

The frontier economies of the Greater Mekong Region (GMR) – Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam – are poised to benefit as the region develops into one of the world’s fastest-growing markets.

The commercial opportunities as Mekong economies climb the manufacturing value chain, factoring in their favourable demographics and strategic location at the crossroads of Asia’s largest markets, are considerable. That said, doing business in these still developing nations – with their variable infrastructure, regulations and approaches to foreign investment – is far from straightforward. What challenges do companies investing in the region face and how should they navigate them? This was the subject of ANZ’s November 2 “Mekong Rising” luncheon in Singapore, which produced a number of insights about how businesses have made their investments in the GMR’s rapidly changing economies a success.

VIETNAM LEADING THE WAY

The GMR is the latest – and probably last – region in Asia to follow the “flying geese” paradigm, which postulates that the production of goods will steadily migrate from more developed to less developed economies as costs in the former rise. Thailand, now a middle-income economy, has long been the regional leader. But more recently Vietnam has shown how the GMR’s frontier economies can rise up the value chain.

Vietnam’s transformation in recent years has been remarkable. Labour and resource-intensive goods comprised around two-thirds of Vietnam’s manufacturing exports as recently as 2010, but by last year they made up just 47%. In 2010 electronics and mobile-phone related products were just 8% of Vietnam’s USD72 billion total exports. Five years later – a period in which Vietnam received almost USD65 billion in FDI, of which 70% went to manufacturing – they made up almost 30% of the country’s total exports of USD162 billion. This performance was even more remarkable considering that in 2014-15 most of the rest of Asia was experiencing a trade recession.

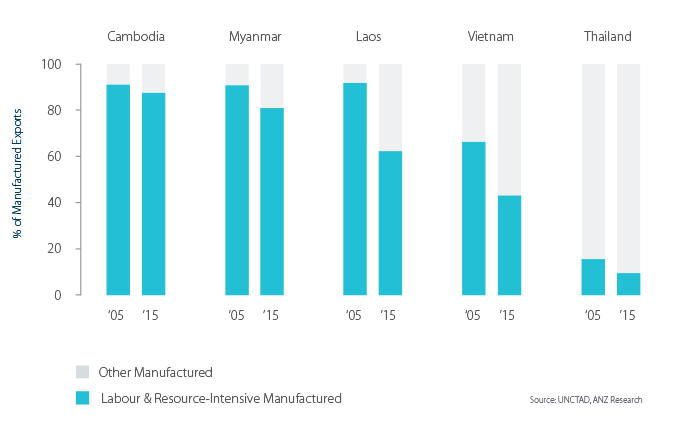

The GMR’s other economies still rely much more heavily on low valued – added manufacturing, but in each the proportion of such exports has also fallen notably in the past decade (Figure 1). While it may not be realistic for the smaller economies of Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar to copy Vietnam directly, they can still benefit from the “flying geese” effect.

This is partly because they are increasingly factored into regional “+1” strategies, in which companies with operations in the more developed Mekong nations seek to take advantage of their neighbours’ competitive labour costs – and develop supply chains across the region. This also means they benefit from the technology and skills transfer that accompanies increased cross-border commerce.

NICE INFRASTRUCTURE, BUT REGULATIONS STILL EVOLVING

Changing trade flows are also playing a crucial part in the GMR’s development. “The frontier Mekong economies recognise that the ASEAN Economic Community and its domestic market is a growing opportunity that they can serve,” said Dennis Hussey, ANZ CEO for the Greater Mekong Region. Increasing global integration, through bilateral and regional trade deals also potentially stand to boost trade to and from the region.

Regional governments realise they are at an inflection point where they can take advantage of the changes sweeping ASEAN to attract investment. Following Vietnam’s lead, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar have taken steps in recent years to improve their investment environments, most notably by developing numerous special economic zones (SEZs) and industrial parks. They have also developed transport corridors (financed by the Asian Development Bank, or ADB) that aim to provide new, faster land routes linking India and China to key ports in Thailand and Vietnam (Figure 2).

To date, though, capacity utilisation of these investments remains disappointingly low, Dr Jayant Menon, Lead Economist for the ADB, said at the ANZ event.

This is because while GMR economies increasingly have the “hardware” in place, in the form of new roads, bridges and ports, they still often lack the “software” necessary to attract greater privatesector use of these facilities. This includes streamlining regulations such as customs procedures and reducing non-tariff barriers, as well as enhancing institutional capacity, rule of law and skills development. “As these get addressed you will see an increase in the usage of the infrastructure as well,” Dr Menon said.

WHY “GREY AREAS” NEEDN’T BE A HINDRANCE

Business leaders at the ANZ discussed that navigating the often “grey” – and in some cases “intentionally grey” – rules and regulations across GMR nations is still a challenge that requires good on-the-ground knowledge. Opaque customs rules and differing transport standards complicate commerce across GMR land borders. “If you ask two government officials in two provinces their interpretation of the same law it will be quite different,” remarked one panellist. Businesses should therefore seek interpretation of those rules and regulations from an official, so they can effectively operate in the region.

Business basics are also sometimes unclear: Chua How Kiat, a partner with Deloitte, explained that despite Myanmar abiding by 2010-era international accounting standards on paper, non-standard practices are still common and rules around deferred tax and what costs are tax deductible are still unclear.

That said, businesses recognise that the investment environment in GMR economies has improved notably in a short space of time. Prakash Jhanwer, Regional Controller for South-East Asia for global agri-business Olam International (which operates across 70 countries worldwide and has been investing in Vietnam since 1998, using it as a base to expand operations into other parts of the GMR) said that SEZs in the country are comparable in quality and the reliability of their utilities to any the company uses in South-East Asia.

Others noted that an increase in road transport has driven up freight volumes, partly as clients in the fast-moving consumer goods and retail sectors increasingly seek distribution via inland routes.

Myanmar has seen perhaps the most dramatic changes in recent years, going from a virtual pariah to Asia’s most exciting untapped market. “The ease of doing business in Myanmar has improved considerably compared to doing business a couple of years back,” said Rajesh Ahuja, ANZ Myanmar CEO, noting that it should already be thought of as an emerging or developing economy rather than a frontier economy.

Indeed, he explained, ANZ clients in a variety of sectors have succeeded in setting up operations there with one heavy engineering plant going from planning to operation in just 10 months, and telecoms firms installing 10,000+ towers nationwide in less than 2 years. However Rajesh also noted that investors still needed a higher risk appetite, due to remaining challenges in Myanmar, such as opaque rules and regulations, and a not yet well developed infrastructure.

The time is right to push into the region. There is tremendous business opportunity.

PLAN FOR THE TALENT CRUNCH

There are some issues that are harder to get around, such as a death of skilled labour. Mr Chua shared the arresting statistic that for a population of 55m people, Myanmar had just 1,200 certified public accountants.

Finding the right talent is perhaps the biggest issue facing investors in GMR economies. This means that when setting up operations, companies will initially need to bring in supervisory or management staff – but must also remember to embed comprehensive training into their cost structures. Since public education, the ADB’s Dr Menon said, should aim to provide “trainable” rather than “trained” labour, the onus is on the private sector to help the young, ambitious and hardworking population develop vocational skills.

The shortage of talent inevitably feeds back in to the “software” issue that complicates doing business in many Mekong nations, with governments lacking the capacity to swiftly implement laws that are enacted. Although the legislation is welcome, since public institutions lack the capacity to impose regularities in execution, or draft supporting bylaws with the required speed, the outlook for their implementation in practice is uncertain at this point in time.

GET GOOD ADVICE — AND DIRTY HANDS

Investors agreed that the challenges of investing in the GMR are clearly outweighed by its potential – with the right preparation. This requires two things in particular. First, on-the-ground experience is crucial. “In the first two years, the incubation period, it’s important to get your hands dirty and really understand every detail of your operations,” Mr Jhanwer advised. Second, securing good on-the-ground advice and building internal expertise, whether around law, tax, or banking, is necessary to help navigate potential bureaucratic complexities.

Businesses forearmed with these two things will be well positioned to take advantage of the improving investment environment in GMR economies. “The time is right to push into the region,” Mr Hussey said. “It is out-performing the rest of Asia in trade development by a factor of two. There are tremendous business opportunities.”

RELATED RESEARCH

research

Wages - And Ambitions - Rise As Mekong Workforce Enters A New Era

Can Mekong countries foster skilled labor while retaining competitiveness?

research

Along The Mekong, A New Regional Network Takes Shape

Transport corridors set to enhance connectivity and accelerate commerce.

Read more

For a full set of relevant disclosures, please visit the link below.

These publications are published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia on its Institutional website.

If you choose to access these materials, you agree that the Website Terms of Use apply. These publications are intended as thought-leadership material. They are not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in these publications is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in these publications constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in these publications is based on information available at the time of publication. While the publications have been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of these publications or the use of information contained in these publications. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with these publications.

If you are resident or located in the United States of America, you agree that you are not acting on behalf of a natural or individual (including yourself) “U.S. person” (as defined in Regulation S of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended) and you agree not to transmit or otherwise send any information on this website to any natural or individual person in the USA or to publications with a general circulation in the USA.

If you are resident or located in New Zealand, you are a “wholesale client” under the Financial Advisers Act 2008 (NZ), as amended.

Please confirm that the above statements are correct.