INSIGHT

Goodbye, Globalisation? The Outlook for Asia in 2017

Download the PDF

By Richard Yetsenga, Chief Economist, ANZ | April, 2017

________

At the start of the year many people were uncertain about the economic outlook for the Asia-Pacific region. The political shocks of 2016, namely Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, reignited debate about the benefits of an open, globalised trading environment. Concerns about the impact this would have on Asia crystallised in questions around US trade policy and China’s ability to spearhead globalisation.

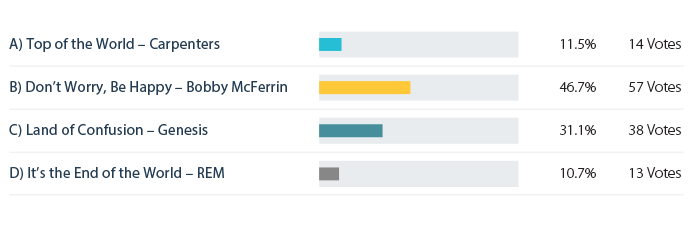

Such issues dominated discussions during the Economic Outlook roundtable events ANZ held in February and early March. The mood of attendees was gauged by a light-hearted question at the beginning of each event: “Which pop song would you associate most with your outlook for 2017?” In Hong Kong, Genesis’s “Land of Confusion” took the most votes, while in Singapore the outlook was more sanguine with Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” coming out on top.

Confusion is understandable, but so is the comparatively relaxed Singaporean outlook. There are several reasons to be confident that Asia can withstand the forces that threaten to buffet the world economy in 2017 and emerge stronger than before. There are also good reasons to doubt that the worst-case scenario — a 1930s-style trade war — will transpire, despite the political sensitivity of the issues and the momentum behind the Trump administration.

A shift in economic power

Taking the long-term view, one reason for optimism is that the world is a vastly different place than it was even a few decades ago. Incontrovertibly, the centre of economic power has shifted in recent generations, in large part thanks to globalisation and technological change, forces that won’t be easily reversed.

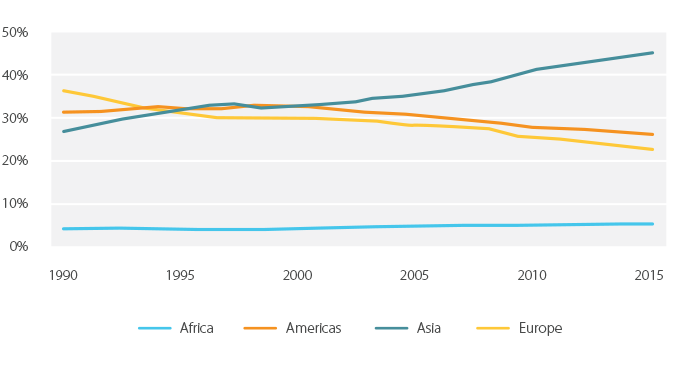

Asia has been the prime beneficiary of these trends: sixty years ago it was the world’s poorest region, but it now accounts for one-third of global GDP and is likely to exceed 50% by 2050. In 1990 more than 60% of East Asia lived in extreme poverty; by 2013 only 3.5% did. In China alone 680 million people escaped extreme poverty between 1981 and 2010. To a large degree, the most successful Asian economies followed similar models — pioneered by postwar Japan — of building up export-focused manufacturing capacity before moving up the technological value chain.

Source: Calculations derived from worldeconomics.com

This development model has had its critics, especially as perceptions have deepened that the US’s massive trade deficit (USD734 billion in 2016, of which China accounted for 47%) has cost jobs. Politically appealing though this claim is, it doesn’t stand up to much scrutiny: analysis by economists such as Harvard’s Dani Rodrik has shown that while trade has played a part in the decline of such jobs, in the developed world these losses have been primarily driven by technology. In 1980 it took 25 jobs to generate USD1 million of manufacturing output in the US; today it takes just five.

The upshot of these trends is that first the US is somewhat less important to the global economy than it has been historically, and second that global commerce is less dependent on the kind of merchandise trade that would be susceptible to damage inflicted by punitive tariffs (to the degree, for instance, imposed by the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which severely exacerbated the Great Depression).

Of course, the US still accounts for a large proportion of final demand — even for trade within Asia, given the complexity of global supply chains — and merchandise-trade-dependent economies, of which there are still plenty in the region, would suffer from a tit-for-tat tariff war. But Mr Trump cannot single-handedly turn back the economic clock.

A sustained global recovery

Taking a shorter-term view, are Singaporean executives right to not worry and be happy about the prospects for 2017? The signs are good that the global economy is indeed in a sustained recovery trend. The boom in equity markets in recent months has been linked to the pro-growth policies promised by Donald Trump (a side-effect of which, incidentally, would be to increase import demand) but its roots are longer and deeper than that.

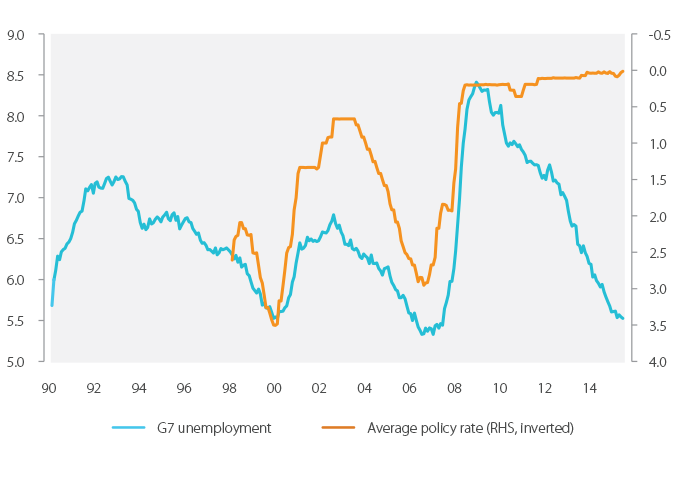

Unemployment in G7 economies, to take one important indicator, has been falling since 2011, the largest and sharpest such fall of recent decades. This doesn’t mean that everyone who wants a job can find one, or even that those in employment have seen appreciable income growth. But it is evidence of a synchronised and sustained global recovery.

To date this has not been followed (as it has in previous cycles) by a normalisation of interest rates. This will change as unemployment rates continue to fall and labour participation rates and wages rise. But with questions still remaining about underlying inflation, no major central banks, including the US Federal Reserve, are showing any inclination to tighten policy aggressively.

To be sure, the Fed is the farthest along in the cycle and is likely to hike rates three times this year. Where does this leave Asia? Fears have been voiced about a repeat of the 2013 “taper tantrum”, when just the suggestion of the end of quantitative easing in the US sent capital flooding out of emerging markets and put a number of Asian currencies under pressure.

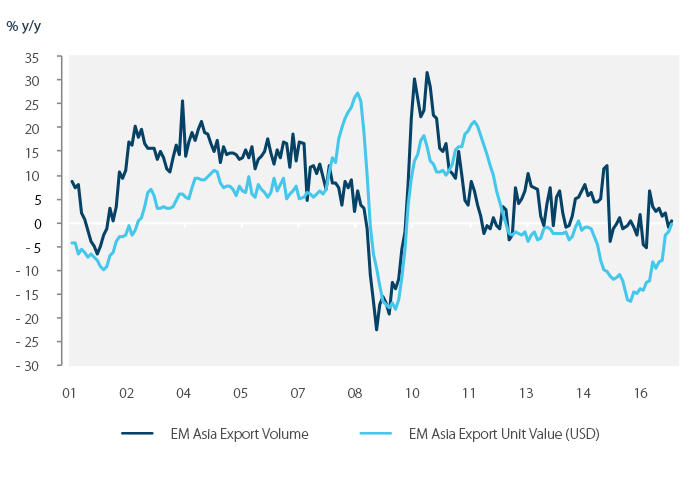

A repeat is highly unlikely, not least because the trade outlook for most Asian economies is improving, helped by an uptick in commodities prices. The collapse of these in 2013, far from being the boost to the global economy many predicted, contributed to weak growth in Asia and reinforced concerns about deflation, prolonging exceptional monetary policy conditions. The situation is different today: commodities prices are rising and, with the exception of those from China, so are Asian exports.

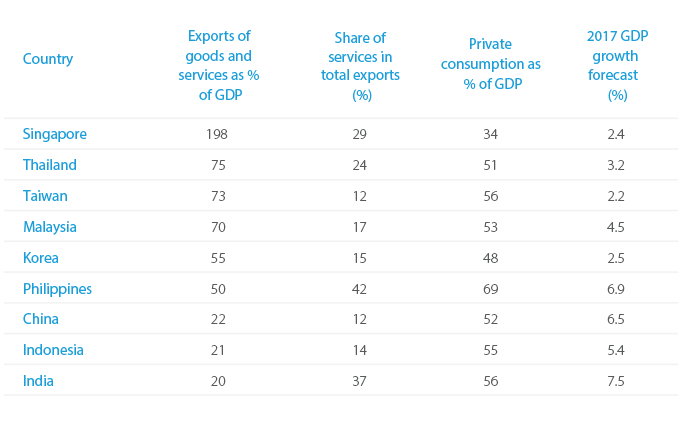

Trade dependency, though, will be an important driver of relative regional performance. Asian economies that are most dependent on exports will continue to underperform through 2017. Those that are more domestically focused, or derive a greater share of their exports from services, are likely to fare better, since trade in the services sectors has been performing much better while merchandise exports have remained weak.

By our forecasts Singapore, in fact, being the most dependent economy on exports, is forecast to post the slowest GDP growth rate in South and South-East Asia at 2.4% in 2017. Conversely India, the Philippines and Indonesia, with their smaller share of exports and greater reliance on consumption, are likely to deliver stronger growth.

Trade, taxes and tantrums

Even if underlying global economic conditions are more benign than they have been in several years, “Trump risk” in the form of a policy shock is still on the cards in 2017. Indeed, aside from withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership the Trump administration hasn’t really begun to tackle one of the president’s favourite campaign issues: trade policy.

What form action on this front will take is open to speculation. Though he promised to impose punitive tariffs on imports from China and Mexico, it is unclear whether the president will be able to muster sufficient support in Congress to take this approach. One reason is that such a measure would end up punishing US companies: the value added on iPhones assembled in China, for example, is minimal, so a tax on the import from China of products back into the US would in effect be a tax on Apple’s profits.

Another proposal with worrying implications are tax reforms that would cut the top-line rate of corporate tax but levy “border adjustments”, such as a 20% tax on imports and exemptions for exporters. Again, getting Congressional support for such a radical plan is uncertain, not least because lobbyists from US net importers like retailers, who rely on low-cost manufacturing abroad (often in Asia), are pitted against those from large American exporters who favour the idea. It would also push up the value of the US dollar, making US exports less competitive.

Regardless of its precise form, some kind of action is certain: the issue will be how other countries respond. Direct tariffs targeting specific countries (China and Mexico) tempts those countries to retaliate, for political reasons as much as economic ones. The tax plan might have a less immediate impact but could still trigger similar policies elsewhere — or, if other countries show due restraint, a long-winded challenge to its legality at the WTO.

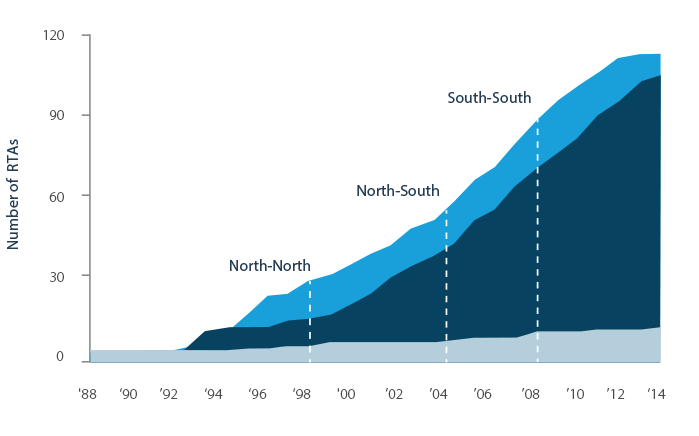

The signs so far have been good that the world does not share Donald Trump’s antipathy for the global trade system that has been built, slowly and painstakingly, since the second world war. It is worth remembering that Washington controls only American trade policy, not global trade policy. Since the late 1980s, the most explosive growth in trade liberalisation has actually been in regional agreements between developing countries.

There is no reason why this will come to a screeching halt. Most of the international reaction to the Trump administration’s plans has reiterated the value of a pluralist global trade regime. Several nations, Australia prominent among them, have suggested the TPP might be worth salvaging even without the US’s involvement. (In fact 11 of the pact’s 12 original members gathered in Chile in mid-March to discuss how this might happen.) Even if the TPP doesn’t proceed, the political oxygen devoted to its passage could easily be transferred to other multilateral deals such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes 16 Asia-Pacific economies.

RCEP might not be as ambitious as the TPP on issues such as intellectual property protection and trade in digital services (which are an increasingly important part of global GDP in their own right). But its lack of ambition might work in its favour, allowing it to survive as a base onto which, over time, more advanced provisions might be built. It’s certainly better than the alternative. Against a background of committed pluralism, the US is more likely to end up isolating itself rather than single-handedly taking the global trading system back decades.

The pivot to China?

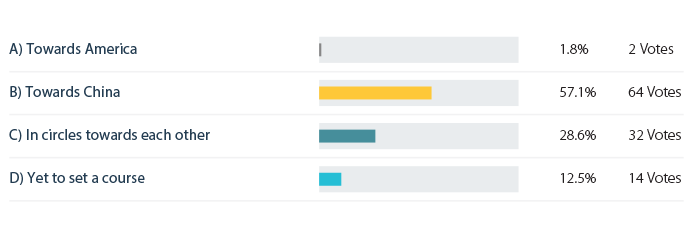

One thing is certain: there will be a much greater focus on China’s role as the champion of multilateral trade deals in particular, and globalisation more generally. It is a role Beijing appears willing to adopt, as evidenced by Xi Jinping’s keynote speech in Davos this year. The rest of Asia, meanwhile, will gravitate towards Beijing, in the opinion of the executives who attended our Economic Outlook events.

Of course this is not a recent phenomenon; the groundwork for China’s “going out” has been laid for years in the form of outbound investment both by state-owned and private companies, and in infrastructure building — now to be conducted on a grand scale through its USD900 billion “One Belt, One Road” scheme. It will continue to be a part of official policy as embodied in the 13th Five Year Plan (2016-20) but also increasingly a corporate imperative, as Chinese companies seek to build their global brands.

China’s evolution into becoming an exporter of capital, after many years of importing it, is entirely natural. But until now its attempts to wield greater power abroad came into oblique or direct conflict with the US’s historical role in the region and the Obama administration’s committed “pivot” to Asia. Trump’s “America First” strategy gives it much more room to manoeuvre.

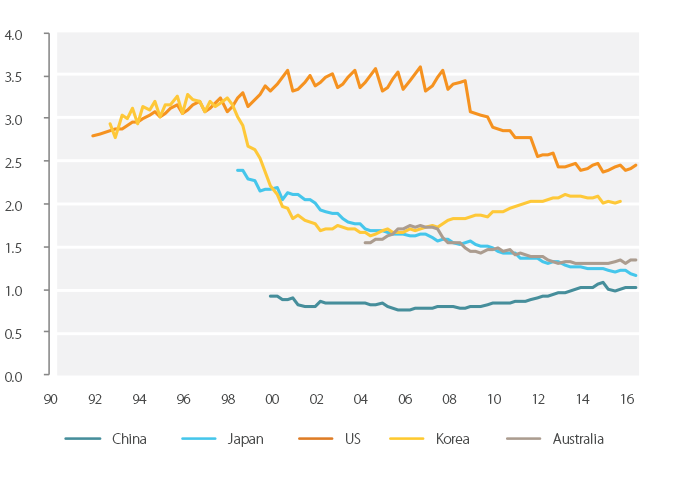

Leaving aside the contentious geopolitical issues that could change the calculus, China-led globalisation will still look very different to the vision formerly led by US. And there are various sound reasons — the limited convertibility of the renminbi, for one — why it is unlikely for many years, if ever, to wield the same kind of preponderant economic power as America, regardless of the overall size of its economy. The fact that is in the midst of a generational domestic economic realignment is another.

Yet looking at the short-term outlook for 2017 this is another reason why Singaporean executives were right to be less pessimistic. In our view China’s economy has demonstrated its resilience in the face of shocks in recent years that would have derailed other economies. Real GDP growth of 6.7% in 2016 is far from slow; nor is the 6.5% target this year, although it does demonstrate the willingness of the government to downplay brute economic growth in favour of more nuanced measures of policy success.

To be sure, China faces numerous domestic challenges as it seeks to rebalance the economy away from its old model. Deleveraging is one. Yet we don’t believe a financial crisis is likely. Compare, for instance, credit to the non-financial sector as a share of deposits in China and in other countries that have experienced crises, most notably South Korea in 1997-98. China is nowhere near that level, although it does face a challenge in moving the economy away from credit and towards equity financing, an adjustment which will be long-drawn-out.

Year of the booster

2017 undoubtedly marks the start of a new era, yet it is not one that economies in the Asia-Pacific need fear. In the short term, while there are many uncertainties, not least the precise form Donald Trump’s trade policy will take, there are plenty of reasons to be positive, in particular because the region is much more resilient to shocks than it has been in recent years.

In the longer term, the forces that have created prosperity in the region are unlikely to be derailed. The emerging market growth story remains compelling, and the Asia-Pacific region in particular will be responsible for an increasingly large proportion of global economic growth.

And, as one distinguished speaker at our events pointed out, if there is one silver lining to the whole “America First” attitude, it is that policymakers within the region will have to recognise their own role in promoting and protecting the gains made in recent years. America will not do it for them. Now more than ever those that have benefited from globalisation will have to become its biggest boosters.

RELATED INSIGHTS AND RESEARCH

insight

No TPP, no problem? Examining Asia’s trade resilience

The politics of anti-globalisation are in the ascendant. US President Donald Trump’s pledges to rip up trade deals and impose border taxes on imports appealed to many voters, as did on the other side of the Atlantic the prospect of the UK’s exit from the EU.

insight

China in 2017: Resilience at home, adversity abroad?

China’s changing economy is robust enough to cope with domestic challenges but a volatile international environment will pose the toughest questions for Beijing’s policymakers.

research

2017: Globalisation in the rear-view

Calls to restore a 20th-century industrial economy will create openings for intra-Asian regional consolidation and digital dominance for China.