INSIGHT

India’s road through the crisis

India’s path through the crisis rests on the resilience of its domestic demand.

The Indian economy was relatively well insulated when the impact of coronavirus, or COVID-19, first gripped markets. At that stage the ordeal was confined to China’s domestic situation and India’s directly affected supply and trade links.

The situation changed as the pandemic has become global. The implications are wide as India accounts for almost 8 per cent of world output.

Added to that, India’s response is somewhat handicapped. The country’s ability to support domestic demand with fiscal and monetary accommodation is constrained and most of all, its under-pressure financial system may restrict the availability of credit for a long time.

Less severe

India hasn’t been subject to a garden-variety crisis. The impact has been less severe than in most countries in three particular respects:

• the scale of non-performing assets (NPA),

• the extent of currency depreciation, and

• the loss in output.

Peak NPAs in the Indian banking system were 12.3 per cent during the 1997 Asian financial crisis (AFC, compared with an average of 30.1 per cent across the region. Peak NPAs in India have also been lower than those in other large economies, including China, Japan, Mexico and Turkey.

The rupee has also been relatively stable thanks to the absence of a large build-up in external liabilities. Neither has growth plummeted as aggressively as it had in most other economies experiencing a financial crisis.

These distinctions however relate only to the acuteness of the crises. But a crisis can exhibit over longer time periods.

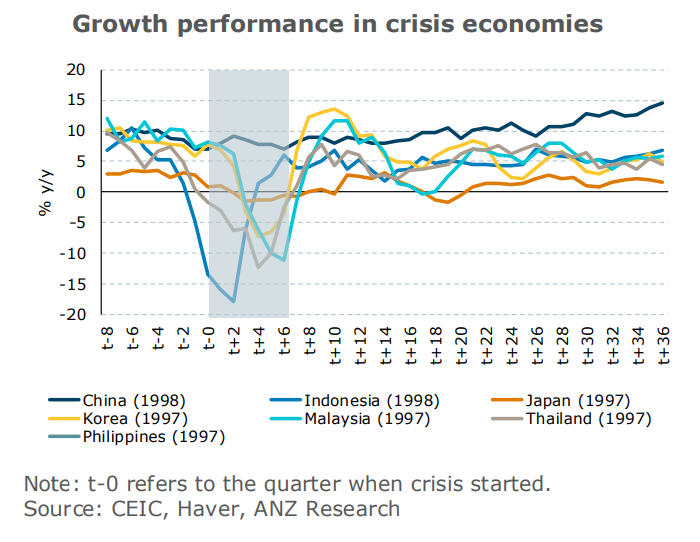

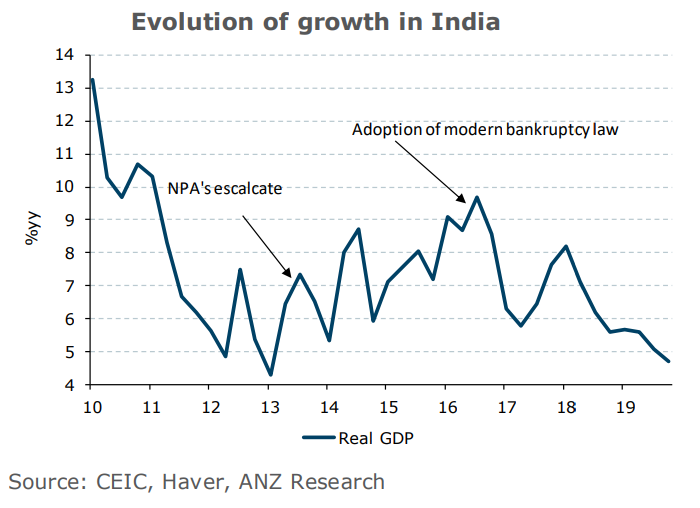

Indeed, growth in India has not suffered an outright contraction, unlike most other crisis-hit economies where growth declined for eight quarters, on average. Yet it has slipped considerably below its trend pace of 7 per cent.

Stresses in non-bank financial companies (NBFCs) also emerged subsequently, although they became apparent only after the collapse of Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services (ILFS) in September 2018.

Initially confined to duration mismatches on their balance sheets, the problems of NBFCs have expanded to worsening asset quality and insufficient capitalisation.

At the same time, other sources of funding, including conventional bank credit, mutual funds and insurance companies, and external borrowings, have not been able to compensate for this.

Against this backdrop, India’s credit-GDP (gross domestic product) gap has widened, once again in consonance with the experience of other economies that have suffered a financial crisis.

In most economies, a large credit-GDP gap persisted for several years even after the financial system was adequately recapitalised, thereby placing the onus of growth on non-credit intensive activities, such as exports.

Finally, a sector-specific problem that has generally accompanied most financial crises is the unravelling of real estate bubbles — this is also becoming apparent in India.

Ahead

There’s a real chance that not only will India’s growth remain sub-trend over the next few years, the trend growth rate itself could reset at a lower level. The most apparent reason is lending standards are and should continue to tighten, owing to regulatory reasons and self-restraint.

A structural tightening in credit is likely to result in structurally lower economic growth, weighing on both investment and, consequently, labour productivity.

Once again this issue is particularly pertinent for India as it has a fast growing labour force, necessitating a continuous increase in capital stock to maintain productivity.

India’s demographic profile is often posited as a structural tailwind for growth. However, if not accompanied by sufficient investment, this tailwind will not only be frittered away but may also engender social discontent and instability.

Furthermore, tighter availability of credit places the onus of growth on less credit intensive activities, such as exports and government spending. With the consolidated public sector deficit running at close to 9 per cent of GDP, the available fiscal space for supporting growth in India is obviously somewhat limited.

India also has a low export-GDP ratio with a further handicap arising from a strong currency. They will constrain India’s growth even after the global economy recovers from the COVID-19 epidemic in our view.

Response

India’s wholesome monetary policy response notwithstanding, the most fundamental issue remains unresolved: risk aversion in the financial sector has yet to decline. Banks need to become comfortable with borrowers and that comfort can only be gauged by the strength of the credit cycle.

Getting to this point will be a multi-year process as has been validated by international experience. As an example, credit growth in the European Union has yet to recover to pre-GFC levels despite the European Central Bank having conducted three rounds of Targeted Long Term Repo (TLTRO) financing.

Since the Indian government infused fresh capital to the tune of 1.7 per cent of GDP into public sector banks and continued with the ongoing consolidation of 27 public sector banks into 12, there has been an improvement in capital positions.

Nonetheless, two issues remain: improving bank governance and achieving a durable reduction in the credit risk being carried by these banks.

Finally, accelerating the resolution of NPAs, which should be at the front and centre of policy efforts, is lagging. The adoption of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) in 2016 was a formidable step intended to ensure bankruptcy cases were legally resolved within 270 days.

The progress has unfortunately slowed as various aspects of the bankruptcy law have been legally challenged. Consequently, the realised resolution time has averaged 374 days, with over a third of the cases exceeding the stipulated time limit.

In ANZ Research’s view, substantial debt resolution is critical, particularly as the current interest rate/economic growth nexus is not conducive to a cyclical reduction.

Complicated

On balance, Indian credit and GDP growth are set to remain weak over the next few years. In fact, the Indian economy may have fallen into a complex feedback loop which will be difficult to exit.

The crisis is chronic. The initial suppression in aggregate demand owing to sparse credit availability has weakened the operating performance and balance-sheet metrics of the corporate sector. This deterioration has, in turn, further added to the reluctance of financial institutions to lend - the end result being excess capacity, limited investment and weak employment generation.

Breaking this loop stretches beyond reducing NPAs or lowering the term structures of interest rates. The entire financial system — not only the banks — will need to be nursed back to health given the inter-connectedness of the institutions within the financial system.

Moreover, risk aversion by financial institutions needs to decline; this can only be achieved by a prolonged period of deleveraging in the corporate sector. The path to lower risk aversion and more credit will be a long one. The international experience is instructive.

Richard Yetsenga is Chief Economist and Sanjay Mathur is Chief Economist, Southeast Asia and India at ANZ

This story is an edited version of an ANZ Research report. You can see the original report HERE.

This publication is published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia. This publication is intended as thought-leadership material. It is not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in this publication is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in this publication constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of publication. While this publication has been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of this publication or the use of information contained in this publication. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with this publication.